Over the last month I have taken deliciously refreshing and salty dips across the Mediterranean: in the Tyrrhenian, the Adriatic, and the Aegean Seas. And while doing so, because one is never far from Rome, I contemplated the Roman fleet which once sailed across what they called the mare nostrum—our sea. It is a reminder that the Roman Empire was fundamentally a Mediterranean, not a European, empire. It once spanned parts of three continents and, both culturally and climatically, Rome had far more in common with Asia Minor, North Africa and Syria than with Britain or Gaul.

One of my jaunts was to Bacoli in the Bay of Pozzuoli, the western-most point of the Gulf of Naples—part of the extremely active Phlegrean Fields super volcano. Pals had rented a house perching on the water, a stone staircase offering direct access into the sea, and kindly invited me along for a few days of bobbing around chatting in the cooling waters of the Marina Grande (which is, happily, not very Grande). From the terrace on top of the house the view looked in a great span from Vesuvius to the tenacious vegetation clinging to the sheer slopes of the Monte di Procida. On the other side is Cape Misenum, the end point of both the Bay of Pozzuoli and the Gulf of Naples.

The Cape is named for Misenus, Aeneas’ trumpeter whose impudent hubris in challenging the gods to a music competition with his conch shell was punished with the wrath of Triton. Aeneas had him buried here before being allowed to enter the Underworld by the Cumaean Sibyl. All this volcanic activity lends itself to dramatic landscapes, redolent of evocative legend intertwined with history.

In the early nineties I was fifteen and studying GCSE Latin in classroom B4, a corner of a Brutalist postwar complex by the ancient city walls of far distant Londinium. Despite my penchant for giggling distraction, which must have been inordinately tiresome, nevertheless the enthusiasms of our patient teacher Miss Perkins filtered through. We read and translated Book VI of the Aeneid in our maroon school uniforms on drizzly London afternoons. The Romantic, warm and hazy mists of Mediterranean legend could not have been further away and appealed enormously, in my mind illustrated by the Romantic, warm and hazy mists of Turner.

As I cooled off in the waters of Pozzuoli—somehow; impossibly—three decades later, I idly contemplated ancient legend as the pleasantly timeless rituals of the Italian seaside acted out around me. As I bobbed I thought of how, beyond the cliff at the end of the beach—past the boys playing football, the elderly ladies taking the early morning sun, the small children being towelled down—Capo Miseno had once been home to the most important base of the Roman Imperial fleet, the largest and most powerful which had ever existed. Sailors from all over the Empire—and indeed beyond: Rome had porous borders, and was only too happy to suck in men from beyond to serve as auxiliaries with the promise of citizenship—passed over these waters.

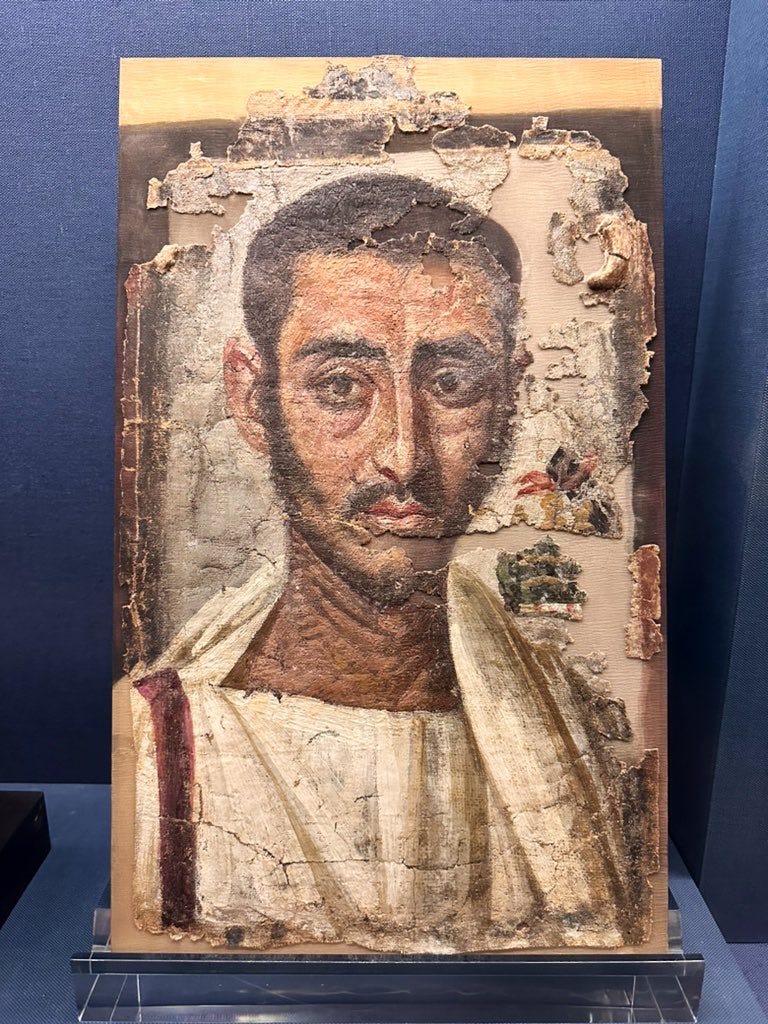

One such sailor, a citizen of Rome from Egypt, was Claudius Terentianus. We know of him from the letters he wrote on papyrus to his father at Karanis, on the edge of the Fayyum oasis, during the reign of Trajan. Their extraordinary survival— such are the vicissitudes of humidity and time—offer a glimpse into the life of an ordinary sailor Frustrated in his attempts to join the Roman army Terentianus had instead joined the far less prestigious and considerably more dangerous navy, serving in the fleet based at Alexandria. Exactly where he served is uncertain: perhaps he formed part of the fleet sent to support the army during the Second Jewish-Roman War, or perhaps he was deployed further east to Trajan’s campaigns in Parthia. Though he almost certainly never sailed across the Bay of Naples I thought of Terentianus, across the Mediterranean nineteen centuries ago; an individual standing for vast numbers of long-forgotten sailors.

From these letters we know he eventually graduated from the fleet to a legion and completed his twenty-five years of service to become a pensioned veteran. As he embarked on his long military career, he wrote this:

And if you are going to send anything, put an address on everything and describe the distinguishing features to me by letter lest any exchange be made en route. And if you write me a letter, address it: “on the liburnian of Neptune.” Know that everything is going well at home, through the beneficence of the gods.

from P.Mich.inv. 5391

Terentianus’ letter-writing was prolific so we can assume he received replies. That such things were successfully delivered is a bafflingly extraordinary feat of administration, if you’d like to go down a rabbit hole of transport times in the Roman Empire may I recommend this fabulous site from Stanford.

As I bobbed in the Marina Grande of Bacoli I thought of the delight such letters and parcels must have brought, and of the tenacity and tenderness of those sailors who once set sail from Cape Misenum just beyond the headland as they waited for post from home.

Less than a month later I was swimming in the even saltier, crystalline waters of the Aegean, off the coast of ancient Euboea. It was from here that, while Romulus was little more than a twinkle in Mars’ eye, the first settlers of Cumae had set sail for Italy. It had all come full circle, because one really is never far from Rome.

Saluti from Rome, Agnes

Please write a book!

Fascinating! Seems like the mail was much better than our current system in the US. Thanks.