In my last post I left Caravaggio fleeing south after the murder of Ranuccio Tomassoni on 28 May 1606; a very literal price on his head. He was helped to abscond by the extremely grand Colonna family, who offered Caravaggio refuge in their feudal strongholds of Paliano, Marino, Zagarolo and Palestrina and created a number of red herrings in Rome to allow him to shake off his pursuers.

Costanza Colonna was particularly important for Caravaggio’s escape. She was the second daughter of the naval hero Marcantonio, who had led the papal forces at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571 (just a few days before Caravaggio’s birth). Costanza had been married to Francesco Sforza, Marchese di Caravaggio and after she was widowed in her twenties had administrated the Sforza interests in the town herself. Before succumbing to plague, Caravaggio’s father had been in the employ of the Marquis and Michelangelo Merisi grew up in the town which would become his epithet. Costanza was some sixty years old by the time of the murder of Tomassoni and was, by all accounts, very fond of Caravaggio.

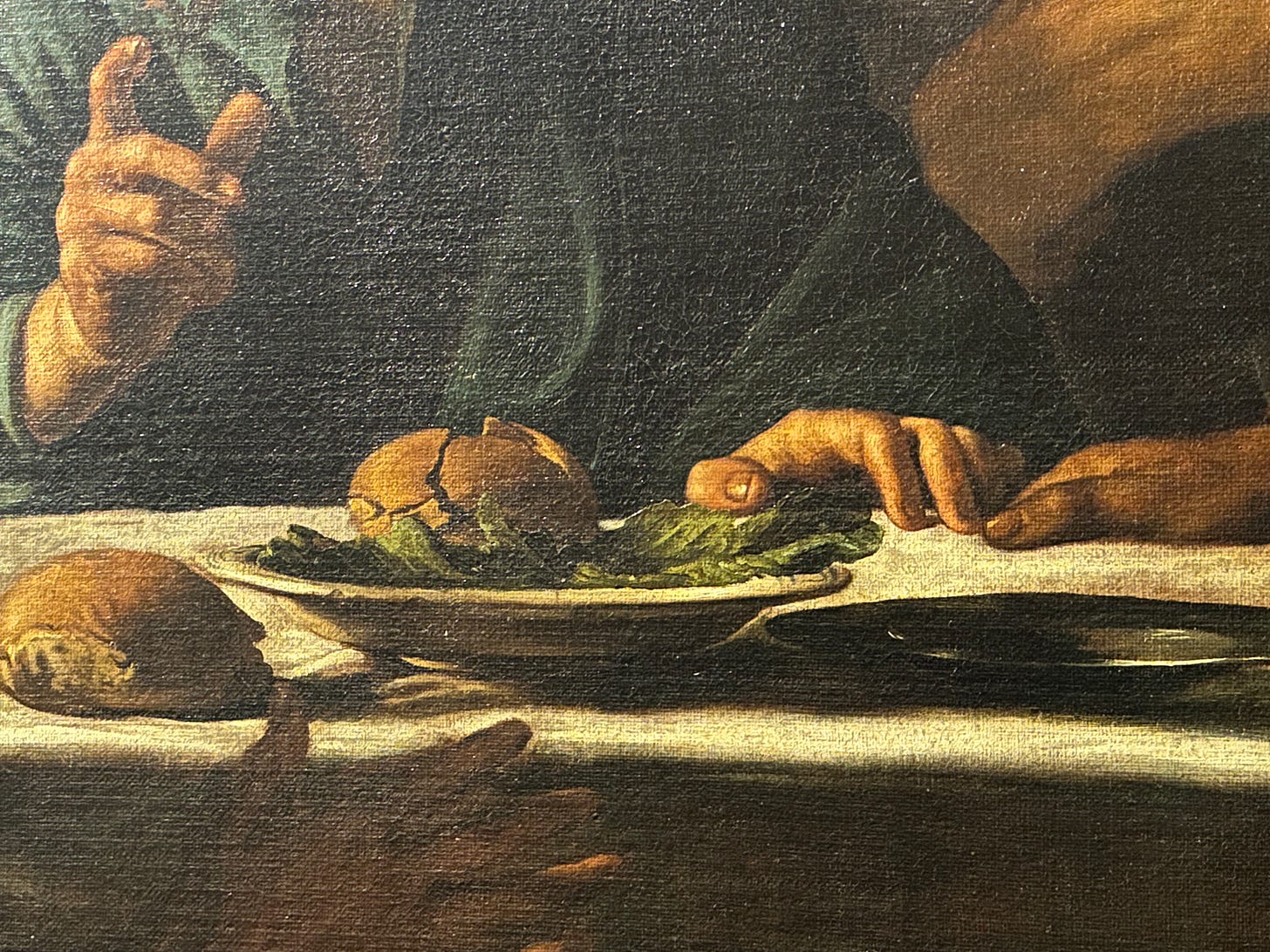

Thus it was that he fled, perhaps first to Palestrina and then to Paliano, hopping between Colonna-owned towns. According to a reference by Bellori in his biography of 1672 it was in this period that Caravaggio painted the Supper at Emmaus, now in the Brera Gallery in Milan.

The scene is that mentioned in the Gospel of Luke (24:13-35) following the opening of the Holy Sepulchre following the Resurrection and is a reiteration of a version now in the National Gallery in London which had been painted for Ciriaco Mattei.

And, behold, two of them went that same day to a village called Emmaus, which was from Jerusalem about threescore furlongs.

The two apostles (which two isn’t specified) there encountered a stranger whom they invited to share their meal.

And it came to pass, as he sat at meat with them, he took bread, and blessed it, and brake, and gave to them. And their eyes were opened, and they knew him; and he vanished out of their sight. Luke 24, King James Version

The moment of the blessing of the bread reveals to them that the apparent stranger is, in fact, Christ.

Perhaps echoing Caravaggio’s own weariness, the Christ shown in this version of the story is quite different to the youthful figure depicted just five or so years earlier. Christ’s face is largely in shadow, but that which we can see is etched with fatigue and sadness: dark hollows sit beneath his downcast eyes; a furrow runs from his nose to his mouth. He is profoundly—almost unbearably movingly—human as he raises his hand in blessing, as if it were a great weight.

To the right of Christ, the florid innkeeper and the deeply wrinkled serving woman are intent on Christ, their brows furrowed. They are incidental characters but are given equal billing with the two apostles, unnamed in the Gospel. Both have their faces turned away from us towards Christ. One shows us only the back of his head, the other—on the right—is in three-quarter profile as he grips the table with force.

His face gleams as the sinews of his neck strain to contain the enormity of the moment: the alchemy of light and life conjured from oil paint upon the weft and weave of the canvas. He is illuminated by the unseen light source which also casts Christ’s shadow on the innkeeper, and which appears to come from behind the viewer’s left shoulder. However, the shadows cast by a bread roll sitting on a large plate and the solid ceramic jug appears, conversely, to fall in our direction. It is as if the source of the light were Christ himself, as per the Gospel of John: “I am the light of the World”.

The St Francis in Meditation, from the permanent collection of Palazzo Barberini, which once hung at the church of San Pietro at Carpineto Romano was probably painted in 1606 during Caravaggio’s stay under the wing of the Colonna at Paliano.

The saint emerges from the shadowy background, a mere idea of a rocky setting to the left of the painting. His battered habit indicates his vow of poverty, and he has just the faintest hint of a halo as he intently contemplates the skull he holds. Below lies a foreshortened crucifix, jutting out towards the viewer and abruptly cut off by the frame of the painting on the right.

Perhaps also painted in this period (though an alternative dating sees it as an offering for Scipione Borghese in return for a papal pardon three years later), the David and Goliath now usually at the Galleria Borghese is a self-portrait. Given the sentence of death by decapitation that awaited him in Rome, the theme is particularly pertinent.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Understanding Rome's Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.