Last weekend we were in London for the kind of casual flying visit that used to be the norm pre-pandemic. There was a family party for my mother’s birthday and we went to Twickenham to watch Italy lose valiantly to England in the Six Nations. We ate very well, walked miles, and managed a visit to the National Gallery where I made a beeline for the Piero della Francesca Nativity which has recently undergone a major restoration, not without controversy.

The painting now hangs by itself in splendid isolation in room 17a, a peaceful oasis removed from the crowds of the main galleries. The small room is painted dark blue which seeks to emulate the prosperous private setting of the bedchamber where it once hung in Piero’s own family palace in Sansepolcro (then called Borgo San Sepolcro).

When the National Gallery bought it in the late nineteenth century it was believed to have hung above an altar it was displayed in a rather grand gilded frame. This has now been replaced with a contemporary walnut frame reflecting its more domestic setting. It was also long believed, erroneously, to be unfinished. In fact the painting was simply extremely damaged, with large areas of the oil paint having flaked off the surface of the poplar panel, damage largely attributable to clumsy attempts at cleaning when it first arrived in England in the nineteenth century.

The painting was painted c.1475 and is one of Piero’s last. Although he lived to 1492, from c.1480 he suffered from failing eyesight and turned his attentions from painting to focus on mathematical treatises concerned with the accurate representation of perspective space, notably De prospectiva pingendi (On the perspective of painting), and De quinque corporibus regularibus (On the five regular solids).

The subject of the painting is a vision described by the fifteenth century mystic, Bridget of Sweden (who founded the first Bridgettine convent in Rome at what is now piazza Farnese). Bridget’s vision would have been well-known to Piero and his contemporaries. She described her vision of the infant Christ lying naked on the ground and emitting light, and the Virgin as blonde and kneeling in prayer having given birth instantaneously, as if light had passed through her with no pain nor assistance required.

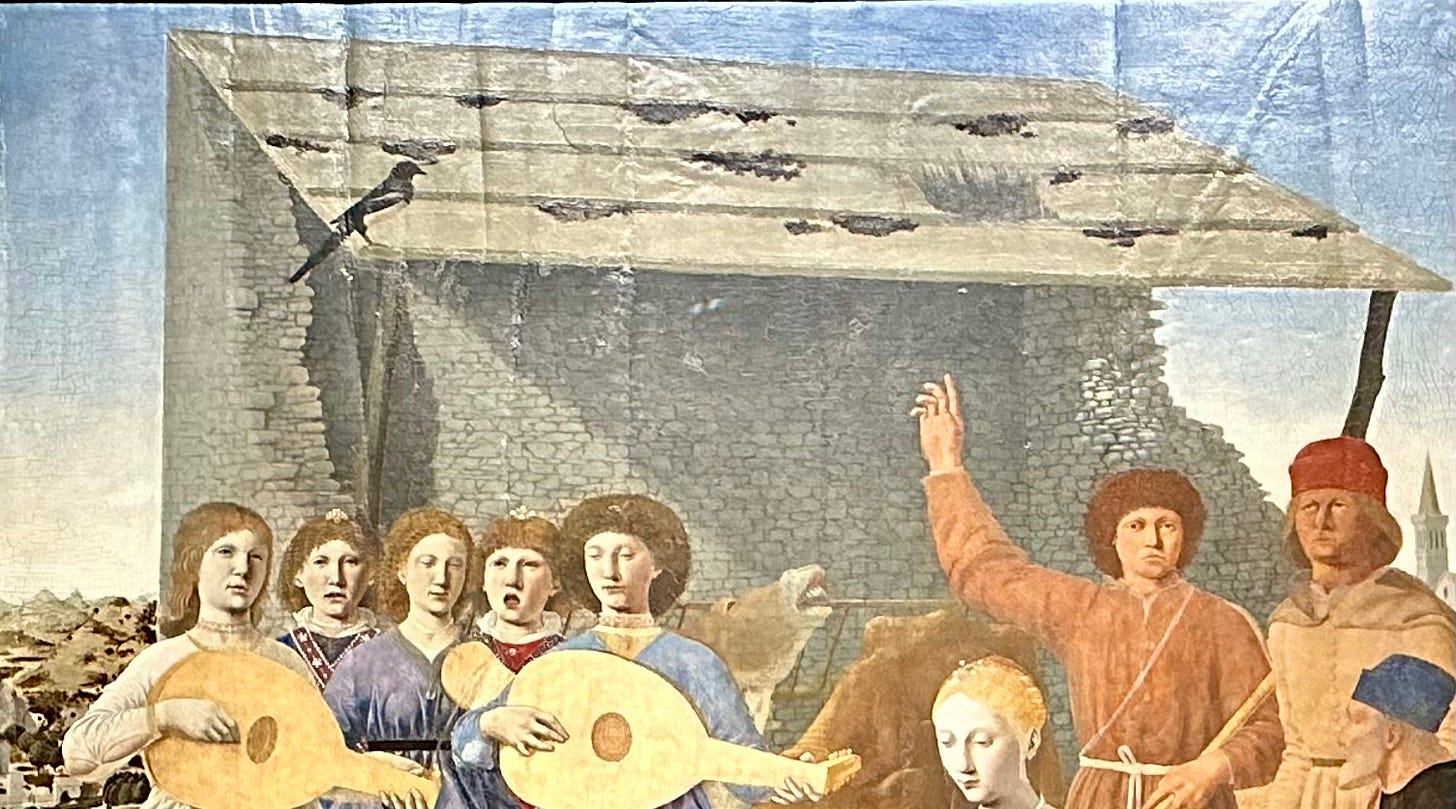

This reference to light is seen in Piero’s painting in a charmingly literal, prosaic way: the roof of the crumbling shelter in the background casts a shadow, and on the stone wall to the right, above the shepherd who points upwards, a patch of light can be traced back to a hole in the roof he indicates. Divine light with a logical source, I love that.

In contrast the exquisite figure of the Virgin is elegant and alabaster as she kneels before the Christ child who lies on the tails of her rich blue robe. Behind, a chorus of angels sing and play their mandolins: fifteenth century Tuscan troubadours in a stance of definite earthly solidity, their tunics billowing around their thighs.

The eldest shepherd, seated on the right, sits with his legs crossed and the sole of his foot jutting towards us in a precociously naturalistic pose in ruddily rustic contrast to the ethereal elegance of the Virgin, his hands clasped.

In the background we don’t see Bethlehem, where the vision appeared before Bridget of Sweden. Instead we see a Tuscan landscape to the left, and to the right the Cathedral of Sansepolcro with its pointed spire is eminently recognisable.

Having admired Piero’s work I emerged from the National Gallery and paused under a glorious blue sky at St Martin-in-the-Fields: a Greek temple pierced by an Anglican spaceship on Trafalgar Square. It is one of the great masterpieces of James Gibbs. Gibbs was an Aberdonian Catholic and in 1703, at the age of twenty-five, was enrolled as a seminarian at the Scots College in Rome. He appears, however, to have had second thoughts and soon after was instead studying architecture under Carlo Fontana. Though he remained a Catholic throughout his successful career he did so quietly, as was then politic.

While in Rome he was exposed to the ebullience of the Roman Baroque and upon his return to Britain translated the effusive extravagances of Bernini and Borromini into an idiom more suited to the Anglicanism and Empire of his patrons. Gibbs’ London church architecture has just a trace of Aberdonian austerity; it is the Baroque made for gunmetal skies. “Great Gibbs of Aberdeen” indeed. I think he is wonderful.

The elegantly severe Portland stone is punctuated with a stern rustication around the windows and doorways, and the interior stucco decoration is accented with occasional dashes of gold which are positively homeopathic when compared to Roman churches.

A century after Gibbs had been a wavering seminarian in Rome, my five times great-grandfather was married in the church. Born in Scotland, married in London, Phillip Shillinglaw appears to have returned to Scotland before emigrating to Australia at the age of sixty-four (then advanced years for such an enterprise, one would assume). He went with some of his offspring and I am a descendant of one of the married daughters who stayed behind. The journey was even more treacherous than they would have had cause to expect: the boat caught fire six hundred miles from land in the South Atlantic, fortune saw most of the passengers saved by a passing ship and taken to Rio de Janeiro from where most proceeded to Australia and Phillip Shillinglaw and his family prospered. A simultaneously everyday and extraordinary tale of emigration researched and beautifully told by my mother here.

As I admired the Italianate stuccoes on Trafalgar Square I contemplated the infinite paths of decisions taken and not, and the ripples they send through time which lead us, generations later, to find ourselves in one place rather than another. As if on cue, as I stood there a snore came from a man sleeping undisturbed stretched out on a pew at the back of the church as the vicar quietly lay out hymnals, careful not to disturb him. It was a stark reminder of the mutability of fortune, so I made a donation to the church’s long established homeless shelter and went out into the sunny February day all set to return to the Roman Baroque.

homeopathic gilding -- bring it on!

a beautiful story of connections/serendipity thank you