Gleaming in the Gloaming: Roman Church Mosaics II

The Birth of Christian Art at Ss Cosma e Damiano

The circular temple to the right of the photo above, lurking behind the last of the second flowering of wisteria in the Roman Forum on a torrid late July day, is traditionally said to have been dedicated to Romulus, the son of the Emperor Maxentius. About a century after the mosaics at Santa Pudenziana (about which I spoke in my last mosaic post), and half a century after the last emperor in Rome had been deposed, the temple was incorporated into the church of Saints Cosmas and Damian by Pope Felix IV (526-30). Cosmas and Damian, the patron saints of doctors, were Roman martyrs who fell victim to the violent persecutions of Diocletian. Born at Aegae in Cilicia (now southern Turkey) and martyred at Cyrrhus in what is now Syria, they were particularly venerated in the Eastern Empire.

When Felix dedicated the basilica in the Forum to the Eastern saints, setting Cosmas and Damian in contrast to the memory of the now defunct pagan cult of Castor and Pollux, he was perhaps seeking to curry favour with Justinian, ruler of the surviving Eastern Roman Empire. Its capital, Constantinople, had been the Greek city of Byzantium. Presumably because “Constantinopolian” doesn’t really trip off the tongue we call this surviving Christian relic of the Roman Empire the Byzantine Empire.

Over a millennium after the church in Rome was built, major modifications were undertaken. These included the narrowing of the apse to make way for new side chapels which rather brutally cut into the mosaics, but the central part of the original apse mosaic survives largely intact.

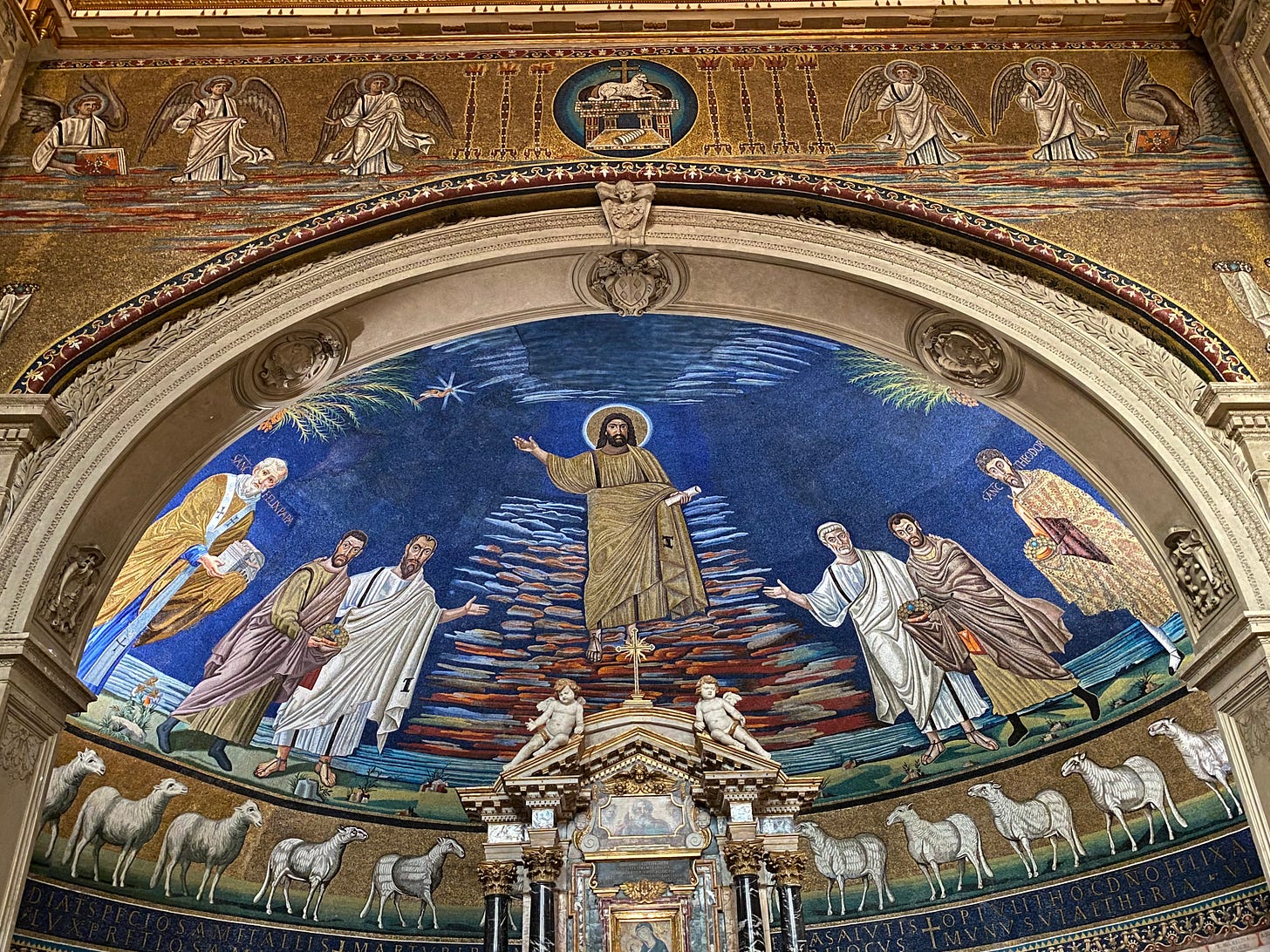

The inscription at the base of the mosaic tells us that, “Felix has offered this gift worthy of the lord bishop so that he may live in the highest vault of the airy heavens.” I rather like the gumption with which he makes this deal with the Almighty.

Dominating the apse is the bearded figure of Christ. A forbidding figure, his right hand, replete with stigmata, is raised to indicate the phoenix in a palm tree. The bird which rose from the ashes becomes in Christian art a symbol of the resurrection.

On either side, and more solidly rooted on earth, are Saints Peter (always shown with white hair) on the right and Paul on the left (always shown with a domed head and a brown beard). Peter presents Cosmas, while Paul presents Damian. On the far right St Theodore lurks nervously, while on the left Pope Felix IV, his face heavily restored, holds a model of the church he dedicated. Below twelve sheep represent the apostles. They form a procession leading towards the agnus dei, the lamb of God, which stands on a rock from which flow the four rivers of paradise, obstructed from view by the much later elaborate marble altarpiece.

We can compare with the mosaics at Santa Pudenziana mentioned in my last mosaic post.

There Christ is involved in discussion, here he is completely removed from the scene. Far larger than the other figures, and neither old nor young, he floats on the fiery flame-coloured clouds in an entirely different realm from the other figures. Indeed they are not looking towards him but out at us; it is as if the Christ figure appears both to them and to us as a communal vision.

While the image of Christ at Santa Pudenziana was distilled from the Roman model of the orator, here we see a figure which has entirely broken the pragmatic shackles of Roman realism. This Christ fully embraces the transcendental nature of Christianity, so different from the Roman religion. I spoke of “Roman Christian-ness” at Santa Pudenziana, this, perhaps for the first time, is a fully Christian art.

If the spirit of naturalism of Roman Imperial art has been transformed into something else, the hierarchy of the Roman world is, nevertheless, still very much present. Christ is robed in a gold toga edged with purple, the inverse of the toga picta (purple embroidered with gold) reserved for victorious generals, consuls, and emperors. The analogy of Imperial power is used to indicate rule over the realm of heaven, of triumph over death. The togas of Peter and Paul mark them out as Romans of substance, but unlike the dynamic realism of the gestures of the apostles at Santa Pudenziana, their poses are identical in their indication of the figure (vision) of Christ. Similarly Cosmas and Damian, dressed as Byzantine princes and bearing the crowns of their martyrdoms, exactly mirror one another. A residual naturalism can be seen in the positions of their feet and the shadows they cast, especially Saints Damian and Paul on the left.

The abstract and formal nature of the apse mosaic at Ss Cosma e Damiano marks the first flowering of a truly Christian art in Rome, filtered through the prism of Byzantium, the surviving Eastern Roman Empire. Too often we are tempted to think of the loss of perspective after the fall of the Roman Empire as just that, a “loss”. There is a persistent and, I’ve always thought, tiresomely banal school of art history - a sort of distillation of the prejudices of Vasari abstracted from the context in which he set them out - which seeks to place value judgements on Late Imperial and Medieval art based on realism; after all an entirely subjective and arbitrary parameter. Are Michelangelo’s figures on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel realistic; is Picasso’s Guernica realistic? The question of success in art is, I’d suggest, rather more complicated; the achievement of representation depends on what is to be represented.

The art of Byzantium, driven by the focus on the divine, the intangible, the future heavenly world, retreated from the classical search for realism (how do you represent heaven?) into a symbolism which could be meditated on by the faithful. The very nature of Christianity, imbued with spiritual transcendence, meant that art did not need to do all the work. Instead it became a tool through which internal visions could be achieved.

The wildly eminent Byzantine art historian (and sometime Professor at my alma mater) David Talbot-Rice uses a wonderful analogy, he speaks of a quotation from the Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Thakur who said of Indian music:

“Our master singers never take the least trouble to make their voices attractive. Those of the audience whose senses have to be satisfied are held to be beneath any self-respecting artist. Those of the audience who are appreciative are content to perfect the song in their own mind by the force of their own feeling.”

Just as the music of which he speaks acts as an impetus which sparks the inner concert of the soul, so the art of Byzantium offers the same formal symbolism, a mantra to provoke meditation on the divine. It’s neither better nor worse, just different.

Basilica of Sts Cosmas and Damian

via dei Fori Imperiali

Open every day 10-1, 3-6. Mass daily at 7.30am.

(Bring change to illuminate the mosaics)

Such a fan of your thoughts about the church mosaics that cross the centuries of Roman history! I can’t wait to revisit Ss Cosma e Damiano again to contemplate the perfection of this altarpiece! 🙌