All photographs are my own, and unless otherwise stated, taken in June 2023.

On the night of the 5th August of 1623, after two sweltering weeks in which the conclave of fifty-four voting cardinals was locked in the Sistine Chapel, Maffeo Barberini was chosen as the successor to the throne of Peter. The four hundredth anniversary of his election is currently being celebrated with a splendid exhibition at Palazzo Barberini, running til 30 July.

Long-mooted reforms of the system of papal election had been established by his predecessor Gregory XV with the bull Aeterni Patris Filius which included the establishment of the papal vote as a secret ballot requiring a two-thirds majority.

The cardinal nephews of Gregory XV and Gregory’s predecessor Paul V—respectively Ludovico Ludovisi and Scipione Borghese—were the front-runners among the papabili (lit. the “popable” candiates) splitting the vote. From the resulting stalemate Maffeo Barberini emerged as a third candidate and was duly elected with the necessary majority. However one of the cardinals, usually thought to be Scipione Borghese, had not cast his vote. To ensure that there be no question over his legitimacy, Maffeo requested the ballot be taken again. This time all votes were cast, and Maffeo was thus duly elected not once but twice. His was a mandate of steel willed, he claimed, by Divine Providence.

Upon his election Maffeo took the regnal name Urban. Pope Urban VIII would rule for just shy of twenty-one years and be one of the most significant patrons of the Roman Baroque. Following the election his family required a palace fitting their new status, and in 1625 the economic difficulties of Cardinal Alessandro Sforza provided the perfect opportunity. The Sforza owned a sixteenth century palazzetto in their garden/vineyard on what were then still the semi-rural north-eastern reaches of Rome which was sold to the Barberini. The project was first overseen by Carlo Maderno, assisted by his nephew Francesco Borromini. When Maderno died in 1629, tenebrous Borromini was overlooked in favour of his infinitely more clubbable contemporary Bernini under whom he continued on the project, which must have stung.

By 1639 the building was completed and Pietro da Cortona, the third man of the Roman Baroque, had completed the vast ceiling of the double-height salone with the dizzying abundance of his Triumph of Divine Providence. The full title of the painting is icastic in its swaggeringly Baroque linguistic exuberance: Trionfo della Divina Provvidenza e il compiersi dei suoi fini sotto il pontificato di Urbano VIII (The Triumph of Divine Providence and its fulfilment during the pontificate of Urban VIII).

In the centre of the ceiling the personification of Divine Providence sits on a substantial cloud. She holds a sceptre and her head emanates light. Slightly above and to the left Immortality, depicted as Urania the Muse of astronomy, proffers a crown of stars. Higher still we see Faith, Hope, and Charity, the Theological Virtues, supporting the crown of laurel within which three vast bees (the crest of the Barberini, writ very large indeed) swarm (if three bees can indeed swarm).

The personification of Glory, or perhaps Religion, supports the keys of Peter and the goddess Roma crowns the crest with the papal tiara. Theological Virtues, Urania, the laurel of Apollo, the keys of Peter, the goddess Roma: it is a fabulous example of the casual cultural cross-pollination which reminds of the inexorable Roman-ness of the Roman Church.

Below this expression of Eternity, the fleeting nature of Time is alluded to by Chronos with his scythe who devours one of his children as the Parcae, the Roman Fates who spin the lives of humans, look on impassively.

The corners of the ceiling are painted with octagonal faux bronze medallions extolling the moral virtues of the Barberini, and all taken from a vehemently pre-Christian past. The noble selflessness of the Roman Republic is called, with not a little irony, to advertise Urban VIII’s reign: the Prudence of Fabius Maximus, the Temperance of Scipio, the Bravery of Mucius Scaevola, the Justice of Titus Manlius.

The painting covers some six hundred square metres, making it the largest painted ceiling in Rome after that of the Sistine Chapel. Like the Sistine ceiling, painted over a century earlier, it employs a framework of painted architecture. However Pietro da Cortona’s ceiling subverts the solidity of Michelangelo’s framework. The High Renaissance spoke of mankind’s ability to comprehend the infinite, and Michelangelo’s design serves neatly to divide the beginning of time into bitesize episodes.

Five years after the ceiling was completed however the seemingly unassailable confidence of the Roman Church came under attack. In October 1517 Martin Luther began his protestations against the corruptions and excesses of Rome. Initially ignored by Rome as the ravings of a crank—a little local difficulty—the Protestant Reformation quickly presented itself as a significant threat to papal power. Within two decades of Luther’s theses, the Council of Trent was called and a Catholic Reformation developed. Emphasis was made on putting the Church’s house in order and (at least in public) the questions of simony, pluralism, and nepotism were to be addressed. Art was to be reigned in; it was to become the handmaiden of religion and the Bible of the illiterate. Exuberant decoration for decoration’s sake was to be halted.

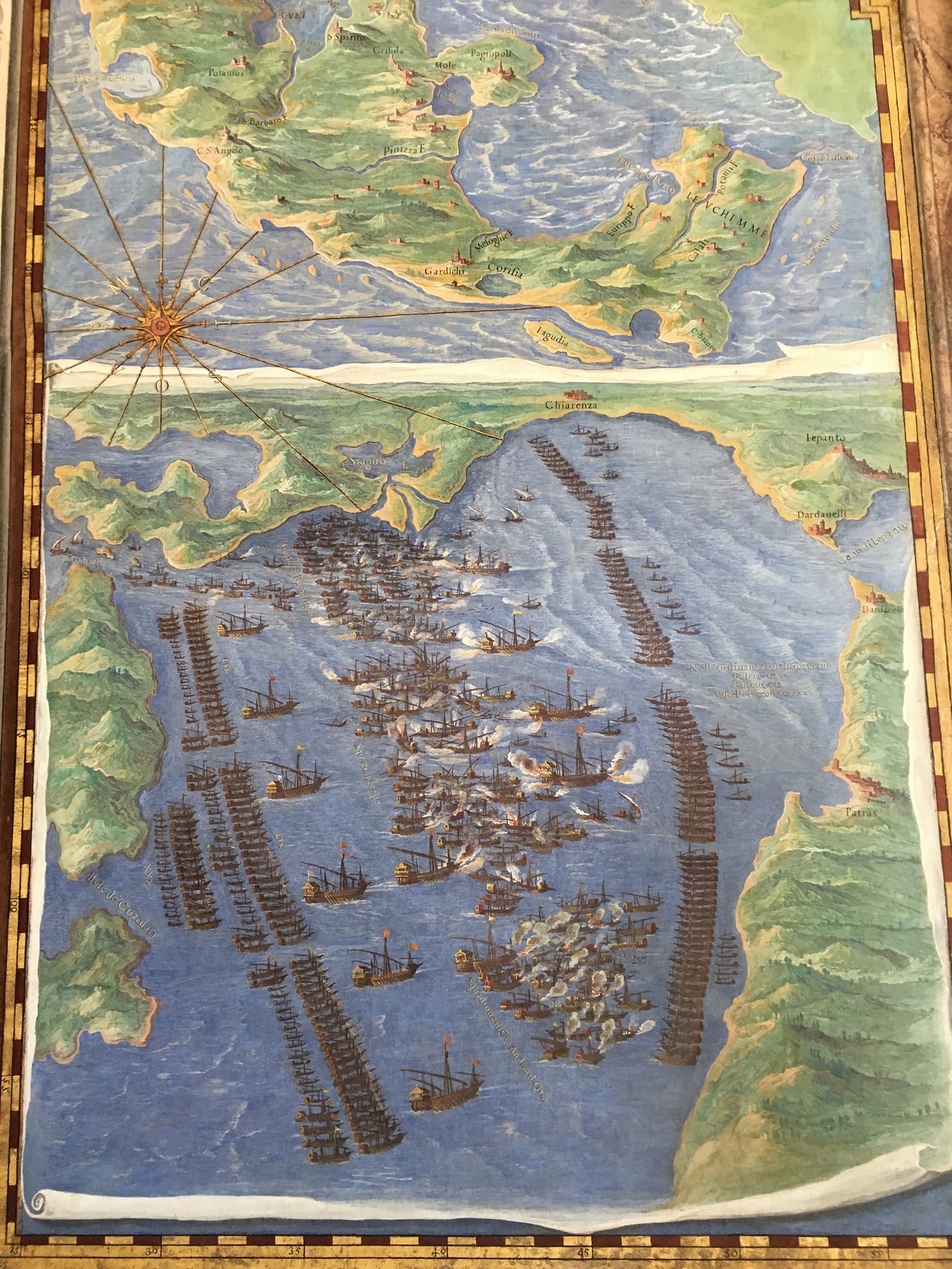

Towards the end of the sixteenth century, however, the mood in Rome began to change. Ever greater quantities of gold from the “New World” were flooding into the papal coffers by way of the Spanish Crown; in 1571 the Battle of Lepanto heralded a change in fortunes as Catholic Europe set aside her differences to rise against a common enemy, roundly defeating the Ottoman Empire.

This new triumphalism saw the Roman Church advertise her might with an artistic style which emphasised miracles and visions. The focus was now on mankind’s inability to comprehend the infinite. One must, says the Baroque, instead surrender to the uncontainable force of the Divine.

Pietro da Cortona’s crumbling painted architecture is powerless to contain the Heavens: he takes the certainty of the High Renaissance as expressed at the Sistine Chapel and sets it in the quicksands of the Seventeenth century. The Baroque is about going over the edges and the ceiling at Palazzo Barberini, which you can almost always have to yourself, is one of its finest examples.

One of my favorite places in Rome . In one photo it looks like they have added chairs for viewing and projected images on the wall. Last time I visited we laid on the floor to view the ceiling ( which I thoroughly enjoyed! ) Thank you for this wonderful article.

I agree with Vivian’s comment! I was enchanted at every turn by my visit to Palazzo Barberini last autumn on your advice!