March's Monthly Newsletter

This week my phone is throwing out a lot of photos of empty places from two years ago, as we were on the cusp of what we now know is called “lockdown” and then was called “quarantine”.

Given current circumstances those strange days seem almost cosy. Though our thoughts (and, more usefully, donations) are with those living cataclysmic upheaval in Ukraine, in Rome things are, however, back to a sort of normal. Masks inside public places and vaccine passports are still very much in order (and if it helps, as it seems to be doing, I’m certainly all for it) but Rome is bustling. Busy as things are I’ll only be doing one new online talk this month, on Saturday 19th March at 7pm CET and repeated on Tuesday 22nd at 11am CET. It will be a continuation of my talk on fountains a couple of months ago and is called Roman Fountains Part 2: From the Trevi to the Aquedotto del Peschiera. I’ll also be doing a live-streamed walk, from via Giulia to the Tiber Island on 18 March at 5pm Rome time.

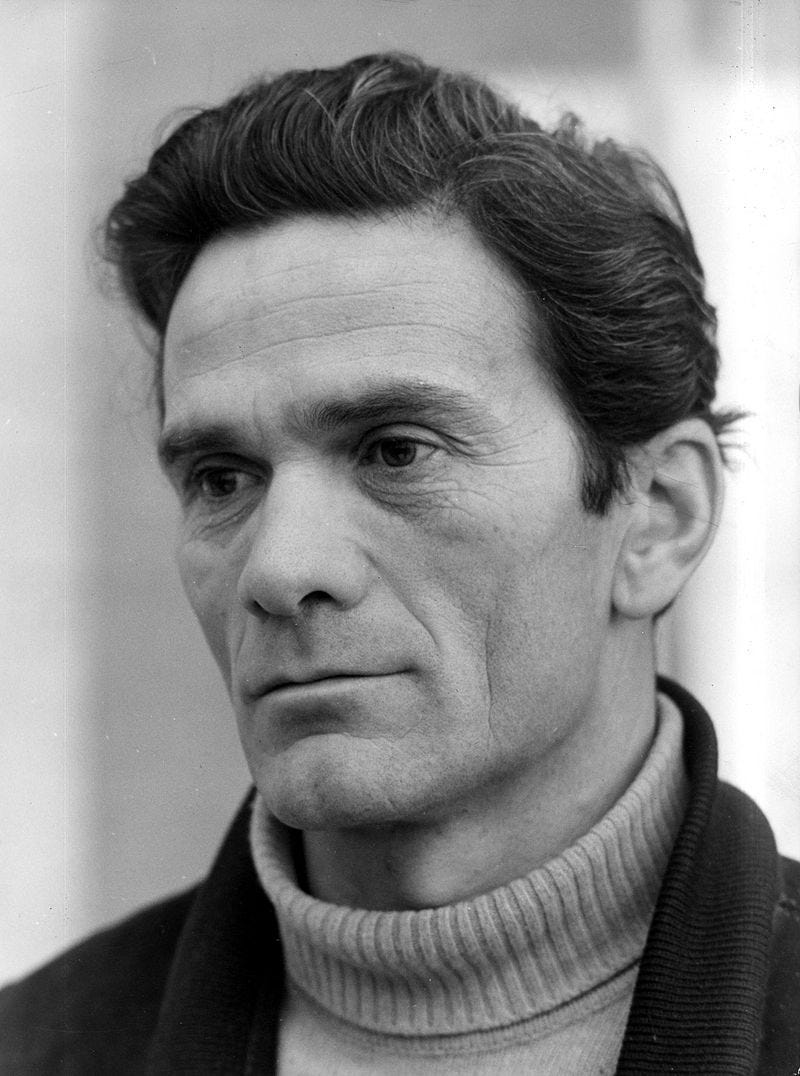

As well as the anniversary of the end of the Before Times, this week also marked the centenary of the birth of Pier Paolo Pasolini, born in Bologna on 5 March 1922. He was a film director, poet, actor, and journalist; like Fellini he was a non-Roman who captured a facet of the soul of the city with dizzying perspicacity. I can highly recommend Stories From the City of God for Pasolini’s Roman writings in English.

Pasolini came to Rome from Friuli at the age of twenty-seven, fleeing charges of indecency (which would subsequently be dropped). “In the winter of 1949, I fled with my mother to Rome, as in a novel”, he wrote. They lived for a period at Rebibbia which was home, then as now, to a high security prison. Immediately after the war Rebibbia was a place of abject and often unsanitary poverty.

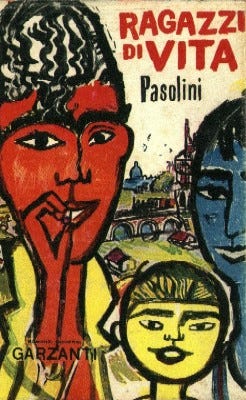

Pasolini’s stark observations of the Roman underclass, which he felt was not merely ignored but entirely invisible to the city’s intelligentsia, were borne of personal experience. In 1955 he published his first novel Ragazzi di Vita (usually translated in English as “The Hustlers”) which dispassionately recounts the directionless lives ensconced in the seamy underbelly of postwar Rome, riddled with petty crime, hunger, casually brutal violence, and prostitution (of both sexes which caused great scandal). The novel is written in slang and without explanation: its neo-Realism is profoundly unedited.

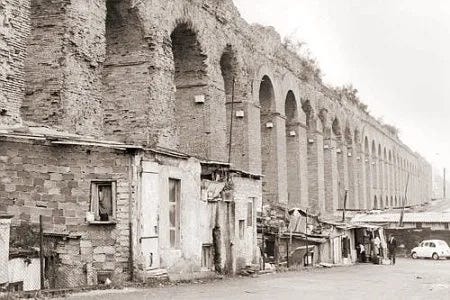

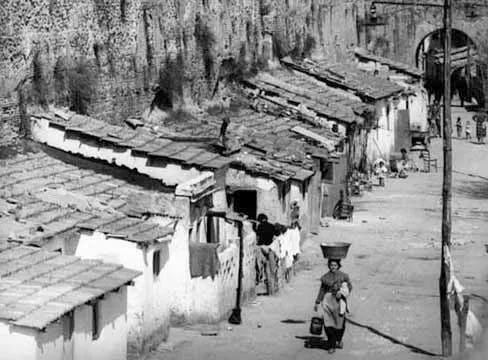

Pasolini also visited other borgate (slums on the outskirts of the city), including that which had grown up along the ancient aqueduct of via del Mandrione. Ad hoc shacks built against the ruins of the once-invincible triumph of Roman imperial engineering were inhabited by people displaced from the neighbouring quartieri of Pigneto and San Lorenzo by the inaccurate Allied bombing of July 1943.

In 1958 he wrote in Vie Nuove (this is my translation):

I recall passing Mandrione one day in a car with two Bolognese friends who were horrified by what they saw. Among the hovels small children played in filthy mud. They were dressed in rags, one even wore a piece of a fur (found who knows where) like a little savage. They ran to and fro, without the rules of any game. They just moved, darting as if they were blind, in those few square metres where they had been born and which they had never left, knowing nothing else of the world than the shack where they slept and the two handsbreadths of slime where they played. Seeing us pass in the car one of them, a little boy, already robust despite being only two or three years old, put his little dirty hand to his mouth and with spontaneous and spirited affection blew us a kiss. […] The unaffected vitality within these souls means a mixing of good and bad in their purest states: violence and abundance, evil and innocence, despite everything.

A few years later he wrote the lyrics of an exquisitely mournful song set to music by Piero Piccioni and intended to be sung by Laura Betti. It’s called Cristo al Mandrione (Christ at Mandrione). This version is sung by Gabriella Ferri

And here are the lyrics in the original Roman dialect interspersed with my translation (I’m afraid I’m no poet):

Ecchime dentro qua

tutta ignuda e fracica

fino all'ossa de guazza

'ntorno a me che c'è?

Quattro muri zozzi, un tavolo, un bidè

I’m in here

Naked and soaked

To the bones with damp

Around me what is there?

Four dirty walls, a table, a washpot

Filame se ce sei Gesu Cristo,

guardeme tutta zozza de pianto,

abbi pietà de me!

Io che nun so gnente

e te er Re dei re!

Lavorà senza mai rifiatà

moro ma l'anima nun sa

Jesus Christ, if you’re there notice me

Look at me all tear-stained

Have pity on me!

I who am noone

And you the King of kings!

Working without taking breath

I’m dying but my soul doesn’t know it.

Filame se ce sei

Gesu Cristo!

Notice me if you’re there

Jesus Christ!

The slums remained along via del Mandrione until the 1970s. Even today traces of paint and plaster and tiles remind us that it wasn’t so very long ago.

Two years ago, as the two month Italian quarantine began, it was along the lonely aqueduct road that I took occasional solitary local walks, and it was there that I watched as the spring of 2020 came and went, and we all wondered what on earth would happen next.

A beautifully poignant reflection. I am ordering "Stories from the City of God" and hope that I will have time to read it before my next visit. Your writing has me missing the Before Times and feeling quite homesick for a place that is not even my home!

A great read! Thanks.