Last month a new museum opened in Rome on the peaceful slopes of the Caelian Hill, a languid stone’s throw from the hubbub of the Colosseum. It is the Museum of the Forma Urbis Romae. Extremely interesting, beautifully displayed and small: what’s not to like? I’m a big fan of a small museum.

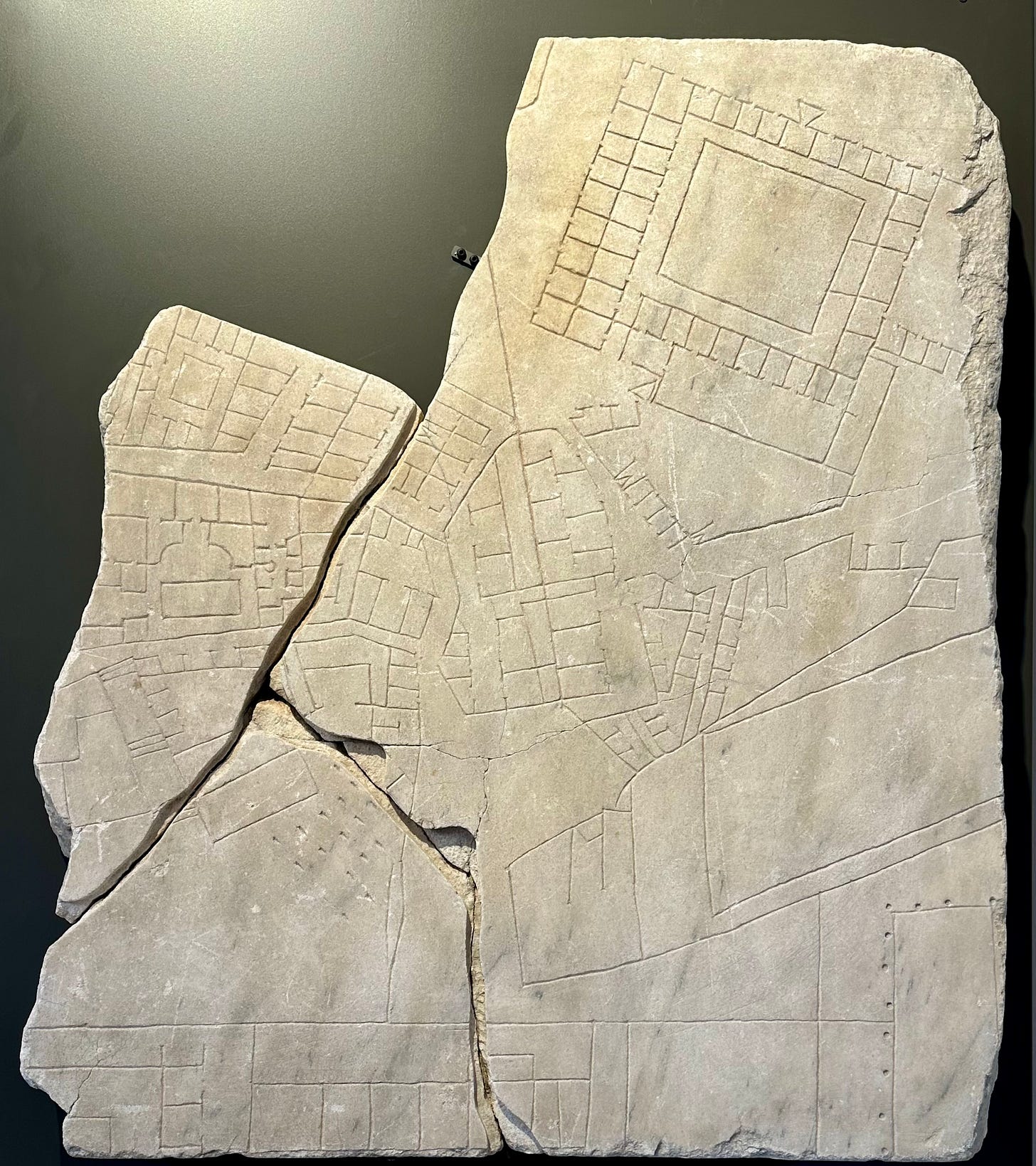

The Forma Urbis Romae was a vast map of the city of Rome inscribed during the reign of Septimius Severus on one hundred and fifty slabs of gleaming Proconnesian marble quarried at the sea of Marmara in modern-day Turkey.

On these slabs the footprint of every building—public and private—in the city was outlined: every column, every staircase and every fountain. These slabs were hung inside the Temple of Peace. This once internal wall is today incorporated in the external wall of the complex of the early sixth century Basilica of Saints Cosma and Damian, the first church to be built in the Forum.

The small holes show where the hooks once held the sections of the map in position, joining the dots is part of the patient detective work which has led to reconstructions of the ancient map.

Work on piecing the surviving fragments together began with the discovery of the first fragments in 1562 by Giovanni Antonio Dosio who was digging for Torquato Conti, an aristocratic soldier of fortune who had bought the excavation rights from the church canons. Torquato’s wife Violante came from a cadet branch of the Farnese family, and presumably in the interests of cementing this alliance with the illustrious papal dynasty the pieces discovered were given to Cardinal Alessandro Farnese.

The pieces were transported according to a contemporary description “by the cartload” to Palazzo Farnese where they were sketched and catalogued by Onofrio Panvinio and Fulvio Orsini, respectively the cardinal’s librarian and antiquarian. Eventually approximately ten percent of the Forma Urbis was recovered. The sixteenth century Codex Ursinius, named for Orsini and housed in the Vatican Library, is made up of drawings by the cardinal’s circle of scholars. They are precise copies to the original scale, and are the source for pieces which have been lost in the intervening four and a half centuries.

The new museum repurposes the long-abandoned gym of the Gioventù Italian del Littorio, the youth movement of the later Fascist period, on the Caelian Hill. A tram line runs past; nearby a slew of sleek Mercedes black minivans are parked as their drivers have a snooze and a sandwich awaiting the call from guides showing their charges around the Colosseum; the corner of the base of the Temple of the Divine Claudius; an extraordinary view of the Arch of Constantine, and of course the ever-present amphitheatre.

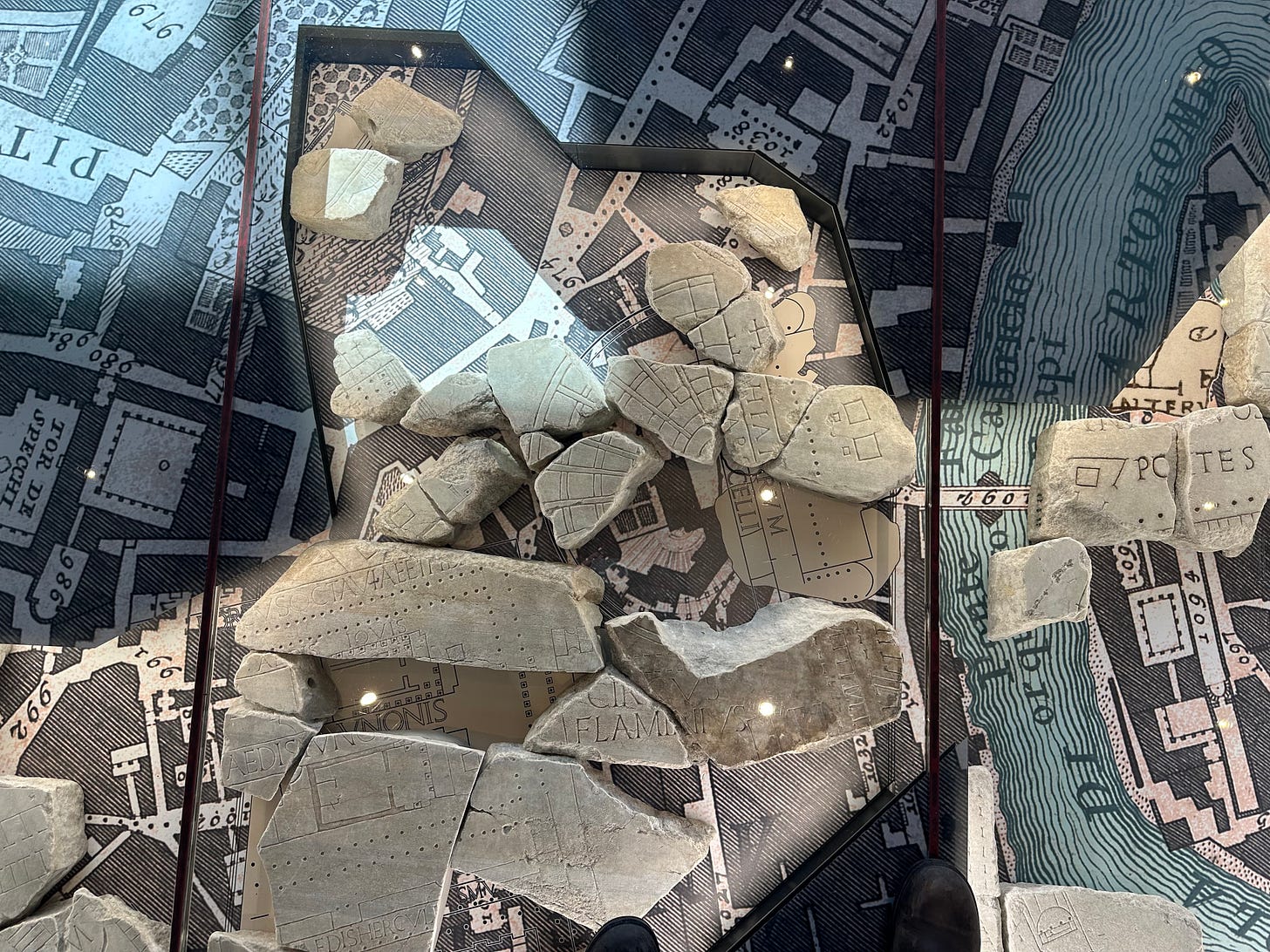

Inside, below a glass floor, surviving pieces of the Forma Urbis are laid atop a vast copy of Giambattista Nolli’s 1748 Pianta Grande, the first accurate scale map of Rome since the Forma Urbis. One walks over the city, placing the ancient fragments in the context of the eighteenth century city (which is, after all, for the most part what the centre of Rome looks like today).

Here are insulae—ancient apartment buildings— in Transtiberim, now Trastevere where in the eighteenth century the papal port of Ripa Grande flourished by the vegetable gardens of the monastery of San Francesco a Ripa;

fragments of the Colosseum and the Ludus Magnus—the gladiator training ground;

glimpses of the temples of what is now Largo Argentina, and the Portico and Theatre of Pompey subsequently hemmed in by San Carlo ai Catinari and Sant’Andrea della Valle;

and here the Basilica Julia in the Roman Forum, in the eighteenth century still known as the Campo Vaccino, “the cow field”.

Cattle and goats grazed, oblivious to the fragments of columns emerging from the centuries of silt and rubble below them. Those partially buried columns are depicted in 1839 by Turner in his view of “Modern Rome: the Campo Vaccino”. The painting is now in the Getty in Los Angeles, but when I was at university it hung in the delightful (and free) National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh.

I often went to visit it when I was a student. On one occasion, with the solipsistic teenage tendency towards bathos, I remember seeking it out for a spot of distraction as I felt sorry for myself after a bit of mildly uncomfortable dentistry. There’s nothing like the collapse of a once invincible Empire to put being nineteen with a Novocained jaw into perspective.

On the left of Turner’s painting, between the columns of the temple of Antoninus Pius (repurposed as the church of San Lorenzo in Miranda) and the tall bell tower of Santa Maria Nova is a hazy glimpse of the church of Saints Cosma and Damian, built incorporating the Temple of Peace where the Forma Urbis once hung.

Walking over the glass of the new museum, the pieces of the ancient map superimposed upon the eighteenth century street plan, is a dizzying experience. For we inevitably superimpose further, multiple, layers upon those places and our experiences connected to them.

I visited midweek and few people were there, all of us wandering over the map in silence, identifying for our own satisfaction places we knew. Each creating a sort of personalised temporal hologram layered upon the third century Forma Urbis and the eighteenth century Nolli map; a panoply of personal recollections linked to these places: whether lived in situ, or perhaps seen through the eyes of Turner in far-flung Scotland at the tail end of the last millennium.

I honestly can’t wait to visit this museum 😍

Fascinating. A must-see if I ever get back.