I know when I visit a city I like to explore neighbourhoods, I expect you do too. This is the first of an occasional series looking at those quartieri di Roma which are within striking distance of the city centre, but which offer glimpses into a lived city.

In Nanni Moretti’s fabulous 1993 film Caro Diario he scooters through deserted Ferragosto streets extolling his favourite quartiere, Garbatella. He likes, he says, to look in people’s houses and makes up film projects to justify his snooping. When asked what it’s about he invents a plot “it’s about a Trotskyist pasticciere in the conformist Italy of the nineteen fifties. It’s a musical”. So Garbatella, called “la Rossa” for its tradition of unions and partisans, always makes me think of Trostkyist pastry chefs breaking into song. It would, as he says, make a super film.

Garbatella was developed as a new district of public housing in the early twentieth century and is located between the vie Ostiense and Cristoforo Colombo, close to the patriarchal basilica of San Paolo Fuori le Mura. San Paolo is one of the seven pilgrim churches (St Peters, St John Lateran, Santa Maria Maggiore, Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, San Lorenzo Fuori le Mura, and San Sebastiano are the others). Via delle Sette Chiese joins San Sebastiano and San Paolo, the furthest flung from the Vatican, so presumably often the last to be visited by those weary pilgrims.

Along this route (also called the via Paradisi) businesses grew to feed, house, and water the lucrative faithful. Tradition tells of one of these osterie which was run with great success by the Garbata Ostella, the charming hostess, or the Garbatella.

After the Unification of Italy, and the establishment of Rome as the new capital in 1871, the city which had so recently shaken off the shackles of papal rule was to be re-established as a modern capital city. Ministries and government buildings were built across the centre of town, and between the river and the via Ostiense a hub of cutting edge technology developed to power the city: a gasworks, a power station, a state-of-the-art abattoir, and the central markets.

There was a further boom in population in Rome following the end of the First World War, and an ambitious plan was hatched to connect the modern port at Ostia Nuova with the city by way of a navigable canal parallel to the Tiber. This was the dream in particular of Paolo Orlando, a civil engineer who was looking very deliberately at returning to the connection between river and coast of Rome’s ancient past. Though the plan for the river port was never realised, the neighbourhood of Garbatella, intended to house the port workers was constructed.

Garbatella’s location was chosen for its airy and healthful position on the hill above the apse of San Paolo, and was championed by Adolfo Apolloni. Although he was mayor of Rome for one year only, he left a great mark on the city. He was a sculptor who had taught in Boston and Rhode Island (where he married his wife Martha), and returned to Rome full of ideas he had encountered in the US. These had, in turn, filtered from Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City Movement, pioneered with the 1898 publication of his book “To-morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform”.

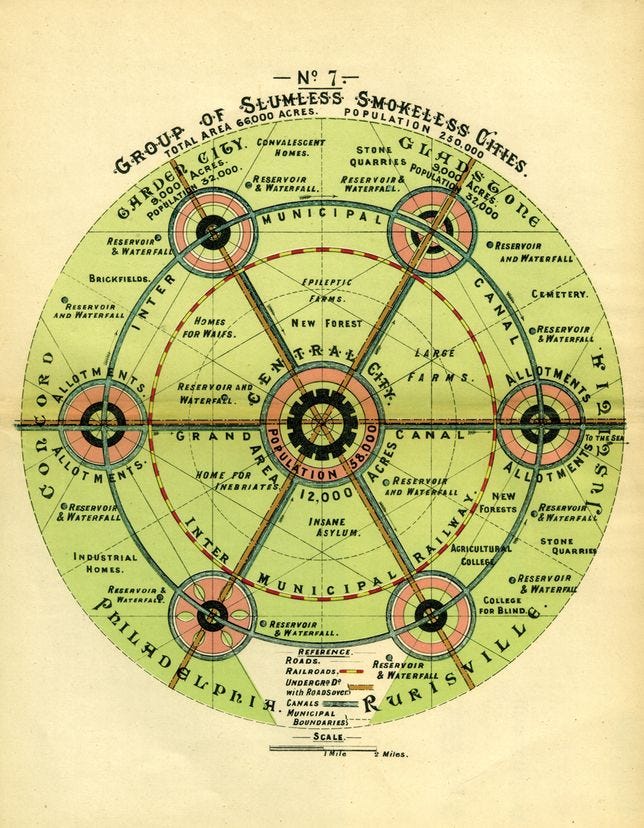

Howard imagined multiple of these “garden cities” as satellites to a central city, all linked by road and rail. The objective was to combine town and country in order to provide the working class with an alternative to farm work or, his words, “crowded and unhealthy cities”. The first to be built was at Letchworth near London but, despite Howard’s original socialist intentions, these leafy and well-connected residential areas swiftly became the bourgeois commuter suburbs they would remain.

In Rome, however, the Istituto delle Case Popolare Romane (ICP), the Rome Institute of Public Housing (founded in 1903) oversaw the building of housing inspired by the Garden City Movement and which remained true to Howard’s ideals. Most notable among these projects was Garbatella. Almost all of this was intended to remain public housing when built with the exception of some houses which were to be a riscatto (paid for by affordable instalments). It is now almost entirely privately owned.

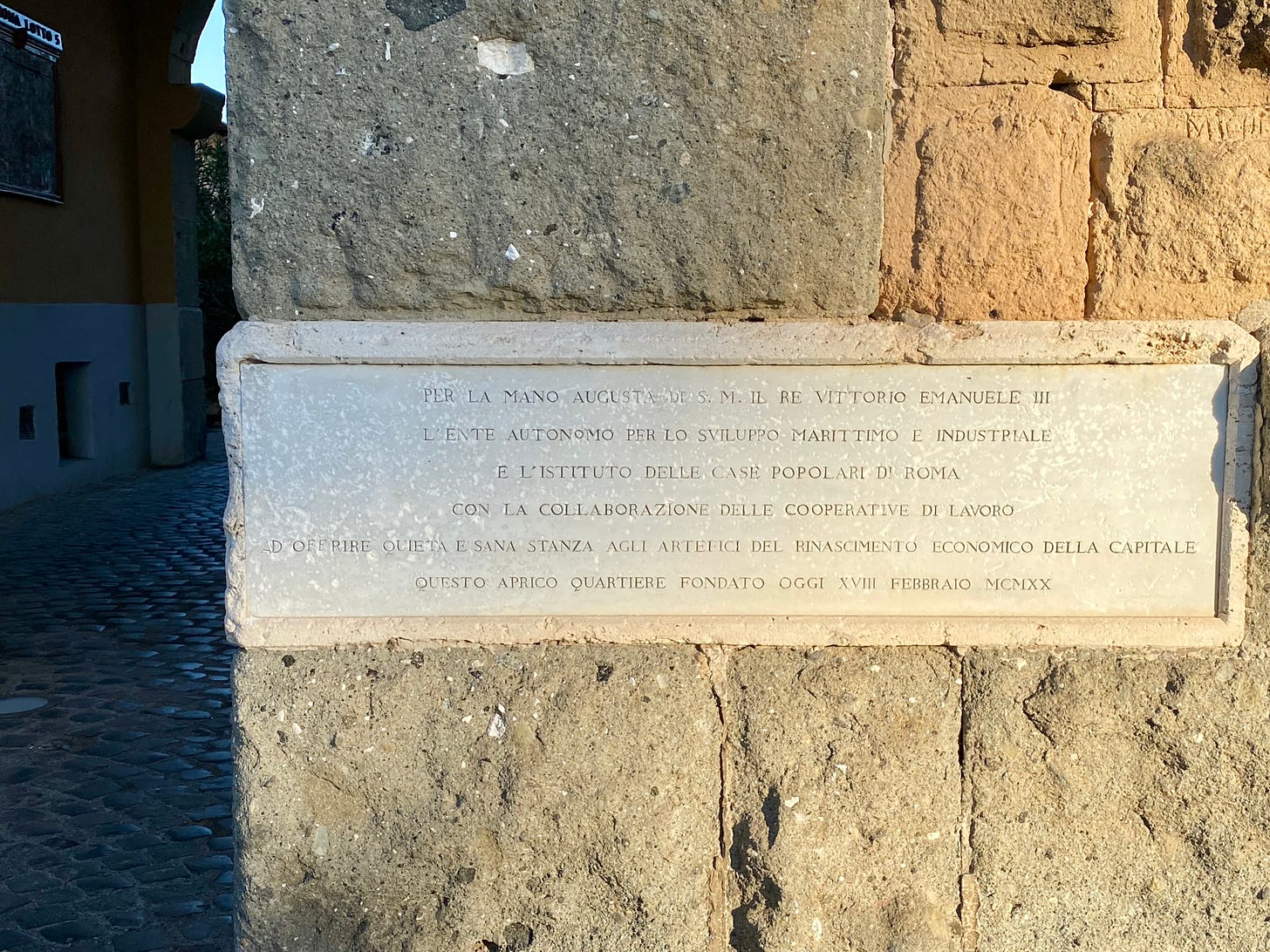

An inscription commemorating the inauguration of the new quartiere on 18 February 1920 can be found to the right of the arch on Piazza Benedetto Brin. The piazza is named for the Torinese naval engineer and subsequently minister of the Navy in the post-Risorgimento Depretis government, a reminder of the workers of the port project which Garbatella was intended to house and the inscription also alludes to this:

“By the august hand of His Majesty King Vittorio Emanuele III,

the Autonomous Body for Maritime and Industrial Development

and the Institute of Public Housing of Rome

with the collaboration of the Workers’ Cooperatives

to offer peaceful and healthy homes to the architects of the economic renaissance of the Capital.

This airy district founded on this day, the 18th February 1920”

This first phase of construction would take place between 1920 and 1930. Although the project was not founded by the Fascist Government, it would swiftly become a Fascist project following the March on Rome exactly a hundred years ago, in late October of 1922.

The blocks of land are divided into lots, and these lotti are numbered. The first lotti (and undoubtedly the most appealing and the most “Garden City”) to be built are by piazza Brin, reached from a staircase from the San Paolo/Tiber. The central building (part of lotto 5) was designed by Innocenzo Sabbatini, a young architect originally from the Marche. At Garbatella, Sabbatini was encouraged to follow the example of the newly built leafy public housing at San Saba with its low-rise buildings and stern mix of Arts and Crafts brick details.

Sabbatini took the eclectic aspect of the Arts and Crafts movement further in the main building on piazza Brin at Garbatella with its deliberately asymmetrical and faux-higgledy piggledy mix of balconies and turrets. A bit medieval, a bit Mannerist: and entirely early twentieth century in its fusion of the two.

Next to the central building of the first phase of construction at Garbatella is an example of a villino (a little villa) design called “type A”, repeated on the site, with a similarly historicizing theme: a building giving the impression of centuries of accretions but designed all in one go.

The ideals of these early buildings with space for family vegetable gardens would give way to cheaper and more densely built blocks as the 1920s wore on but Howard’s idea of a self-sufficient neighbourhood with abundant public space was realised. Schools, public baths, a theatre, and (not part of the original plan) a church the construction of which was funded directly by the Vatican, and certainly not the city.

I can highly recommend that you take the metro to Garbatella, walk up to piazza Brin, and amble through the arch amidst gardens and down the hill to piazza Bartolomeo Romano to the old school Bar Foschi for a coffee and a cake, or if it’s time for something more substantial to the Ristoro degli Angeli next door. For a study of Garbatella’s twenty-first century fauna Tre di Tutto is open every day 7.30am-1am from breakfast to cocktails. And for a modern setting where the Trotskyite pastry chef would feel at home, La Casetta Rossa has a cafe/restaurant which does lunch and dinner Tues-Sat, lunch only on Sun, and holds community events.

Fascinating! Looking forward to more in this series.

Revisiting Garbatella is on the cards after reading this. Thank you for a most interesting post as always. Looking forward to more in this series