I was alerted by a tweet from my pal (and quondam Head Girl) Dr Sophie Hay to an exhibition at the Fondazione Prada in Milan called Recycling Beauty which then still had a week to run. The tweet in question referred to the reconstruction of the Colossus of Constantine which once stood in the Basilica of Maxentius in the Roman Forum.

Somehow, despite being about the repurposing of antique art in Medieval and Renaissance contexts (which is very much my bag), the exhibition had entirely escaped my attention. Serendipitously I found myself with a couple of free days before the show’s last weekend so I went to Milan on the pleasant three hour Frecciarossa train ride. While I was there I also squeezed in return visits for the first time in years to see the Last Supper, Michelangelo’s Rondanini Pietà, and the Pinacoteca di Brera more of which anon.

The Fondazione Prada is south of the city centre, a Rem Koolhaas conversion of a former gin distillery. Straight off the train and onto the Metro, I emerged at the curiously named Lodi TIBB station (I googled it: the TIBB stands for Tecnomasio Italiano Brown Boveri, an early twentieth century iteration of a pioneering producer of industrial electrical equipment founded in the 1860s which had factories nearby).

I arrived under the kind of boundless, all-enveloping, gunmetal skies which make Romans who move to Milan (or indeed Brussels or Manchester) weep. A Spanish friend of mine who lived in the UK for a long time says it was like living in Tupperware which is exactly right. The thing is I grew up under those Tupperware skies and rather like them. So as I sought out the Fondazione Prada in a bleakly post-industrial landscape peppered with leafless trees amid the building sites and railway lines of Porta Romana I felt strangely at home.

The exhibition is co-curated by the eminent art historian and archeologist Salvatore Settis and interests itself with the nature of antiquity repurposed in time. It addresses the question of those disparate temporalities (and the arbitrary nature of the calendars we use to mark them). One extremely interesting piece is a statue of St Joseph created from a head of Antoninus Pius and the body of a Roman flamen, two separate statues dating from the second century subsequently assembled and with the addition of a flowering rod (now lost, here represented by a wooden version) transformed into St Joseph. Are any of these incarnations “truer” than any others?

In his exhibition catalogue essay (here is an online excerpt) Short Circuits, When (Art) History Collapses, Settis speaks of the distinction between the contemporary and the coeval made by Wilhelm Pinder (who distinguishes between gleichzeitig and gleichaltrig). Settis uses the comparison between Cranach the Younger, born 1515, and Leonardo, born 1452. Leonardo may seem to us more “modern” than Cranach; temporality in the most literal sense is not always useful.

Settis goes on to discuss the nature of overlapping temporalities, something I’ve long found extremely interesting. His discussion reminded me of Freud’s reference to Rome in the introduction to Civilisation and its Discontents in which he alludes to Rome as an analogy for human memory:

…let us make the fantastic supposition that Rome were not a human dwelling-place, but a mental entity with just as long and varied a past history: that is, in which nothing once constructed had perished, and all the earlier stages of development had survived alongside the latest...

His is a view of antiquity inevitably intertwined with contemporary thought: it is inextricably informed by Einstein and Picasso; but also by the legacy of Baudelaire, Marx and Darwin.

Freud continues:

Where the Coliseum stands now, we could at the same time admire Nero’s Golden House; on the Piazza of the Pantheon we should find not only the Pantheon of today as bequeathed to us by Hadrian, but on the same site also Agrippa’s original edifice; indeed, the same ground would support the church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva and the old temple over which it was built. And the observer would need merely to shift the focus of his eyes, perhaps, or change his position, in order to call up a view of either the one or the other.

Just as Rome offers this hologram of centuries, its multiple incarnations co-existing, so the exhibition brings together pieces which simultaneously occupy multiple moments in history. They are all beautifully displayed in the Fondazione Prada complex which is itself is a reinvention, in this case of an industrial rather than an Antique past.

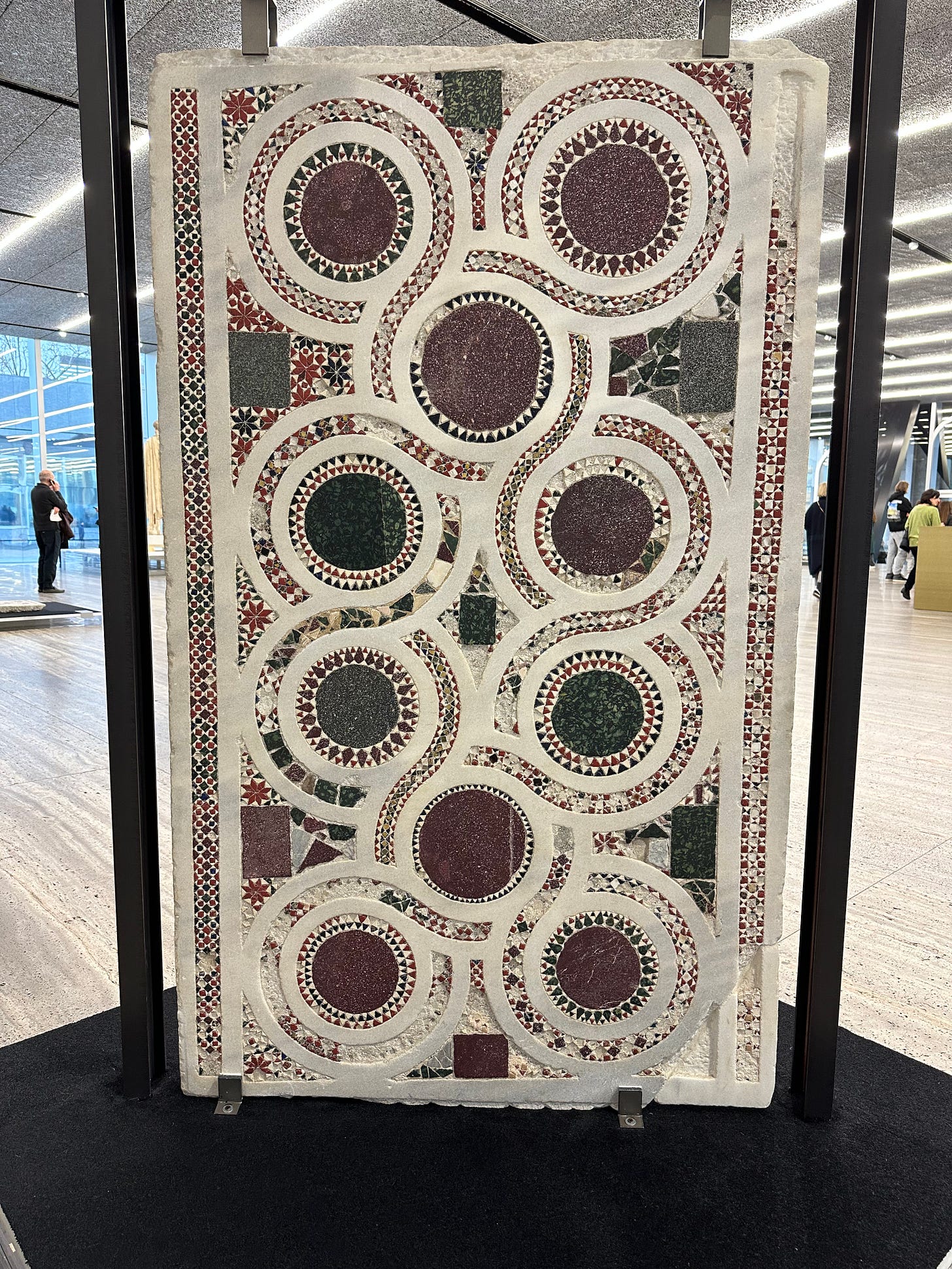

Scattered throughout the exhibition are several examples of “Cosmati” work, on loan from the Cathedral at Anagni. Cosmatesque decoration, as I have mentioned elsewhere, is one of my favourite things and I am reminded that I haven’t been to the glorious cathedral at Anagni in years. They were the perfect punctuation to a thought-provoking show. Here are just a few from the panoply of excellent pieces, many of which are old favourites on loan from Roman collections.

This gilded peacock is one of a pair, on loan from the Braccio Nuovo of the Vatican Museums. It once guarded the Mausoleum of Hadrian (later the Castel Sant’ Angelo, another extraordinary example of metamorphosis), a symbol for the Romans of eternal life.

By the eighth century the peacocks were already part of the decoration of a fountain in the courtyard in front of Old St Peter’s which reused the vast bronze pine cone from the Baths of Agrippa. The pine cone fountain was seen in that courtyard by Dante and is mentioned in the Divine Comedy (“his face was as long and as fat”, says Dante of Nimrod, both anachronistically and unflatteringly, “as the pine cone of St Peter’s in Rome”). The peacocks once associated with Juno and eternal life would (like the phoenix) be given a new Christian reading and become associated with resurrection.

Two Greek kraters (vast vases for the mixing of water and wine) on display come from Pisa and the Archeological Museum in Naples.

The Naples krater of Bacchus dates to c. 50 BCE and is carved from Pentelic marble. It is signed by Salpion of Athens and tells of the infancy of the god of wine. It was subsequently taken to the Cathedral of Gaeta to serve as a baptismal font, with the infant Bacchus becoming the Christ child. No need for any modification to the carving of the baby, it is sufficient for “the observer…merely to shift the focus of his eyes” as per Freud in the earlier quotation.

On loan from Trier, the Ada Gospels are so called for an inscription dedicated to Charlemagne’s sister Ada. Their dating oscillates around the year 800.

The current binding dates to 1499 which can be seen in the eccentric hybrid use of Roman numerals the bottom of the inscription: the first part, M CCCC, follows elegant high Roman tradition (rather than the “sloppier” CD), while XCIX uses this later Imperial “shorthand” with XC and IX standing for 90 and 9 respectively.

In the centre is a cameo depicting the family of Constantine, the emperor who decriminalised Christianity. The cameo appears to pre-date 328 as it features Constantine’s mother Helena on the left. Although Constantine’s personal religious affiliations are less than certain, Helena was certainly a Christian and is a particularly significant figure in the early Roman church for her pilgrimage to the Holy Land, and for the bountiful wealth of relics with which she returned to Rome. Nearly half a millennium after it was made, the cameo was probably already incorporated into the original Carolingian binding (as Charlemagne was hailed in Rome as the new Constantine), before being reemployed in this glorious cut and paste of bling both ancient and modern at the very tail end of the fifteenth century.

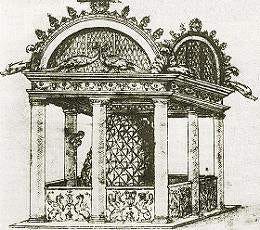

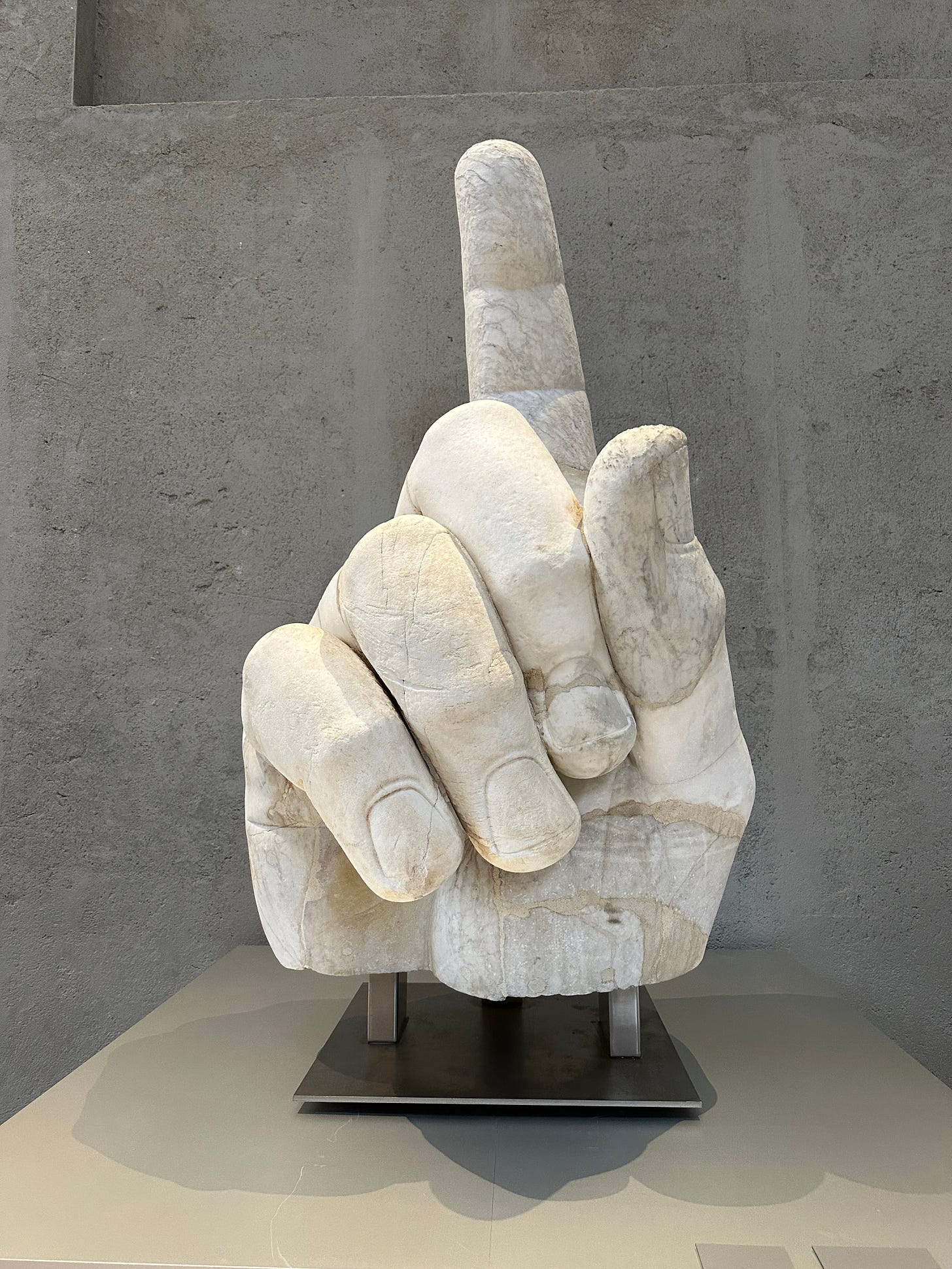

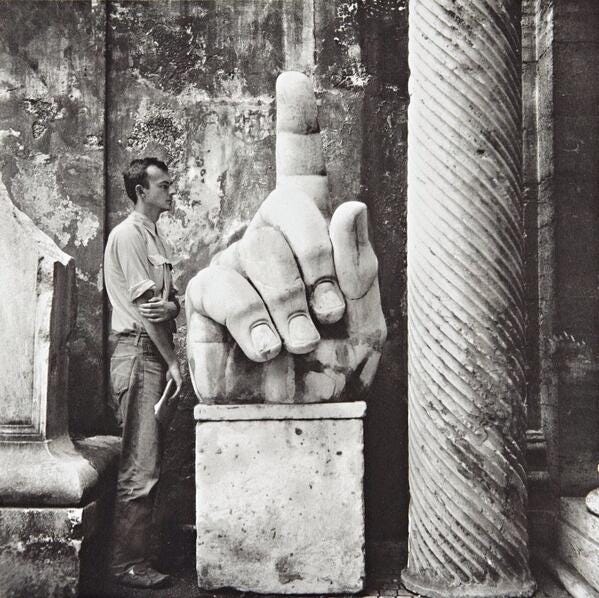

The Colossal statue of Constantine which was the piece which drew me to Milan in the first instance was displayed in the Cisterna, which once housed distillery tanks. Casts made from the surviving fragments at the Capitoline Museums have been integrated with a theorised reconstruction of the vast seated statue which is very probably the reworking of an older statue of a god, here hypothesised (and I’m not sure I’m convinced) to have been the statue of Capitoline Jupiter.

The first pieces of the Colossus were moved to the Palazzo dei Conservatori in 1471 as part of the donation by Sixtus IV to the city of Rome of ancient pieces until then in the Lateran Palaces. Fragments of the Colossus of Constantine thus form part of the collection of the world’s first public museum.

The way the pieces have been viewed, together with changes to their configuration and location, are then also part of the story of the Colossus. In various moments it has been both an hypothesised religious statue and a monument alluding to the Emperor as living god (if he were a Christian I think we can safely say that Constantine was fairly muddled about what that meant exactly). Subsequently its fragments became first symbols of the authority of a papal city which had risen from the ashes of Empire before becoming relics of a crumbled ancient past, baffling in its grandeur.

The colossus reconstructed in a former gin distillery amid a tangle of railway lines is Ozymandias writ large.

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

This sounds an absolutely fascinating exhibition. So glad you got to see and share it with us

The New York Review of Books has just (April 2023) published an essay by Ingrid D. Rowland about this show:

Mysteries of Use and Reuse

For the artists and patrons of medieval and early modern Rome, the repurposing of ancient objects involved a tangle of complex motives.

https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2023/05/11/mysteries-of-use-and-reuse-recycling-beauty-ingrid-rowland/?utm_source=nybooks&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=email-share