Almost exactly four years ago I gave my first online talk on Zoom and it was called “Salt, the She Wolf, and Spin”. I figured the beginning was a good place to start, so I took a deep breath and that’s what I did. My choice of opening subject was also centred on my enthusiasm for the way legend and fact dovetail, something I have long found appealing and spend a great deal of time thinking about.

I think here we encounter a profound cultural difference between a more flexible Mediterranean view of legend and the rigidity of Protestant Northern Europe. Regardless of one’s religious beliefs, or absence thereof, the Protestant stamp left across Northern Europe and by extension also upon—for example—North America is deeply felt. There are far fewer grey areas, things are black or white, true or false. But did Romulus really exist? we may ask in frustration, as if a skeleton might be found telling us how tall he was or how good his dental health was. It is, instead, useful to surrender oneself to the legend. Whether Romulus was an individual who founded the city on the Palatine Hill is really neither here nor there; what interests us is that the Romans believed him to have existed.

The story of Rome’s origins is well-known. Babies in a basket abandoned in a river, a wicked uncle, a wolf, fratricide. Nutritionally improbable cross-species suckling aside, it is a tale of rivalry and destiny as old as the (seven) hills.

This hazy legend is, however, rooted in the solid geographical, geological, and anthropological foundations of Rome’s history: a distillation of fact into a memorable tale modified and distorted over millennia, and harnessed in the service of multiple political agenda, most notably that of Augustus more of whom shortly.

And so whether Romulus or Remus did in fact exist and were indeed suckled by a wolf matters rather less than the fact that the Romans believed this to have happened. All that is solid and eminently tangible in the city—concrete and brick, arches and domes—is built upon the shifting sands of legend. History and myth are inextricably intertwined.

The legends of Rome’s beginnings go all the way back to the Fall of Troy. Writing in the fifth century BCE, in his Histories, the Greek historian Herodotus tells us the Trojan War took place eight hundred years before his time, which would give a date of about 1250 BCE. The story of the fall of Troy is, of course, another example of the oral tradition; of embellishment and distortion over many centuries. Among the numerous characters which feature in the epic tale, one mentioned by Homer in the Iliad (written c.1200 BCE) is Aeneas, the great-grandson of Ilus, founder of Troy. Aeneas’ father, Anchises, is a mortal. A cousin of Priam, the King of Troy. His mother on the other hand was—as mothers of heroes so often are—a goddess. In this case the goddess of love: Aphrodite for the Greeks, Venus for the Romans. In the Iliad Aeneas is a supporting character, however it would be Roman culture which would catapult him into the role of a leading man, and they would adopt his story to be their own. Aeneas would become the ancient ancestor of Rome.

In Roman literature, one of the first major examples of the legend transformed into record is in the second century BCE, in a long-lost book by a man who vehemently railed against the extravagant excesses of Hellenistic culture, Marcus Portius Cato. Undoubtedly this is not his invention, but in his Origines he is influential in setting down in record the idea of Aeneas as Rome’s proto-founder, a baton which, as we will see, would be taken up with gusto by Virgil.

The Roman version of the Trojan War tells us that after the tragic fall of Troy, precipitated by that dastardly wooden horse filled with Greek soldiers, Aeneas is saved from both death and enslavement and is commanded by the gods to escape with his father, Anchises, and his son, Ascanius Iulius.

This is an all-male road trip, Aeneas quickly mislays his wife (and second cousin) Creusa, daughter of Priam, seen here falling behind in Barocci’s grand painting. Retracing his steps to find her, Aeneas encounters a vision of his wife who urges him to take their young son and make a journey across “vast stretches of sea” to “where the Lydian Tiber flows with gentle sweep” where he will become a king and find a royal wife.

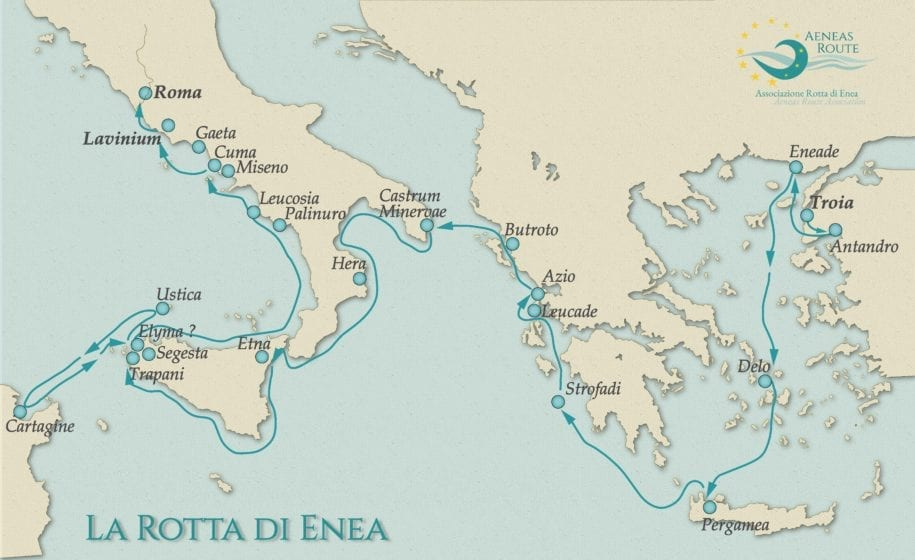

And so he embarks on the sort of interminable zigzagging across the Mediterranean so favoured in classical literature. There are tussles between the gods, some on Team Aeneas (like Aphrodite, goddess of love - Venus for the Romans), others most definitely not like Venus’ arch rival Juno. It is a tale I first encountered when reading the Aeneid at school for GCSE Latin and one I always found captivating, even at fifteen. The retracing of Aeneas’ journey is part of Margaret Drabble’s 2002 novel The Seven Sisters which I read when it was published soon after I had first started giving tours in Rome. The eccentric tour company which plans the trip and the guide who leads it were, I feel, enormously influential in establishing a seed of an idea of how I too would like to work.

After innumerable tribulations Aeneas arrived on the west coast of central Italy, where he is said to have landed there is a beach club called the “Port of Aeneas”. In the Mediterranean classical culture is all-pervasive, it’s even stamped on sun loungers.

Aeneas married Lavinia, only child of Latinus, king of the Latins (a royal wife and a kingdom just as had been predicted by Creusa). He founded a settlement just inland called Lavinium. There’s a small but lovely museum on the site of ancient Lavinium and, each time I’ve been I’ve been the only visitor which only makes it more evocative: a glimpse of legend on an unlikely rather bleak and scrappy road between an unlovely shopping mall and a pretty medieval fortification.

Tradition says that it was Ascanius Iulius who founded the settlement of Albalonga along the ridge of the crater of Lake Albano. Here we can imagine the scene becoming hazy, leaves of a calendar falling, some time later dot dot dot etc.

Umpteen generations down the line, a direct descendent of Aeneas, was the king of Albalonga, Numitor. He was a good king, but had a wicked brother, Amulius. Amulius killed the good king and the good king’s sons, and only the daughter Rhea Silvia was spared on condition that she become a priestess dedicated to Vesta, goddess of the hearth. Thus the wicked uncle figured he would avoid any of her offspring laying claim to his throne.

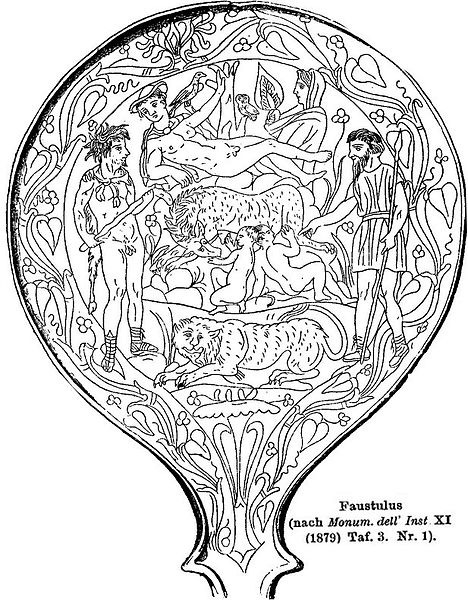

However, he wasn’t counting on the intervention of Mars—god of War—who had his wicked way with Rhea Silvia. She gave birth to twin sons: Romulus and Remus. This is the first known depiction of the twins, a fourth century BCE Etruscan mirror of which this is a nineteenth century drawing (a photograph of the dark bronze reveals little of the slight etching that remains). It is now in the collection of the Antiquarium of the Roman Forum. There is here no mention of Aeneas, the Romans weren’t yet looking for grander divine ancestor; the idea of the pre-historic aboriginal founders wasn’t yet too “primitive” for them.

The later “official” version of the story would, however, see Romulus and Remus not only as the true claimants to the throne but also descended from the gods going further back than Mars. Clearly something had to be done with them. So, because there are only so many stories and babies in baskets in rivers is one, the wicked king Amulius ordered his slaves that the babies be abandoned to their destiny in the Tiber.

Either because the slaves took pity on the children and left them in a basket at the slow flowing edge of the river in flood, or because it was their destiny, or probably – as usual – a bit of both they floated safely into the inlet of the Velabrum. Here they lodged in a fig-tree and were found by the famous she-wolf who suckled them. (There’s the improbable cross-species nutrition). Romulus and Remus grew up and began to argue about who should be in charge.

Remus founded his settlement on the Aventine, Romulus on the Palatine. After various signs of divine will—most commonly mentioned is augury, the study of the flight of birds—the story tells that Remus climbed the Palatine Hill and stepped over the fortifications built by his brother, the so-called Roma Quadrata “Square Rome”. Legend recounts that on the 21 April of the year 753 BCE, which is I think we can agree very specific for a legend, this threw Romulus into a rage by his brother’s impudence and slew him. It is not a very nice story.

And so Roma was named after her first king. Whether or not Romulus was an individual ruler, or whether he is an amalgam of multiple rulers, archeological evidence of increased numbers of burials in the eighth century BCE does tell us of a sudden growth in population, and a settlement on the corner of the Palatine Hill overlooking the Velabrum, and the valley of the Tiber.

If we leave the existence or not of Romulus to one side for a moment, this is a very sensible place to found a settlement: a high point obviously is important for defensive purposes, also in the archaic site of what would become Rome the low land was marshy and insanitary. From the salt marshes at the ostium (mouth) of the Tiber, salt was Rome’s first tradeable good—fundamental for curing food and surviving the winter, was brought upriver. Just below the Tiber Island the river was fordable so there was a serendipitous cluster of high points overlooking a natural hub which allowed trading with the Etruscans across the river and the Sabines to the north east. The road which would develop, the very first Roman road, long before the Appian Way was the first paved road, was the via Salaria: the Salt Way.

In legend Romulus is followed by another six kings (seven is of course a good number). King number four, Ancus Martius, is credited both with building the Sublician bridge, formalizing this crossing over Tiber, and also with founding the port of Ostia. Tarquinius Priscus, king number five, is credited with draining both the Circus Maximus and the valley that became the Forum and creating the Cloaca Maxima which still today takes rainfall from the city drains into the river. For semi-legendary figures, they’re surprisingly practical.

The hazy legend of the kingdom emerges into actual nuts and bolts, flesh and blood, definitely happened history shortly before what we now call five hundred BCE. The last king of Rome, Tarquinius Superbus, was overthrown and a new system of government instituted in its place. A relative democracy, the res pubblica: government as a public matter.

The city continued to grow across the seven hills we know today (those seven hills are was only established by Varro in the first century BCE; the ancient Septimontium was more a vague concept than a geographical one: seven planets, seven kings, seven heights).

Five centuries of expansion across Italy and beyond began, a search for a more noble foundation story with more ancient and divine ancestry began to justify this expansion. The last century of the Republic was plagued by civil war, and from these damaging internal struggles emerged a populist aristocrat whose military prowess and ruthlessness were matched by his illustrious lineage. Julius Caesar and his family, the gens Iulius, claimed descent from Ascanius Iulius, son of Aeneas. What better right to rule? Caesar’s plans were, of course, ultimately thwarted by the conspiracy of the Ides of March of 44 BCE. His death left a vacuum which would ultimately (after a seventeen year campaign) be filled by his great-nephew, Octavian, who had been adopted as Caesar’s heir.

At the age of thirty-six, seventeen years after Caesar’s death, Octavian would be given a new title by the Senate. He would be proclaimed Augustus, a title until then used as a fairly obscure honorific with religious overtones. It was an extremely smart move: he was not proclaimed as king, but rather took a title which had not been held in this context by anyone before. It was both totally modern, and yet rooted in the archaic and the priestly, with its overtones of venerability and augury; it sounded ancient but had none of the autocratic connotations of an ancient monarchic title. It’s an extraordinary bit of spin.

Under Augustus the multiple strands of the legends of Rome’s origins would be woven into a tapestry which served to exalt his right to rule, and the glorious destiny of his reign.

Augustus’ house would be built on the corner of the Palatine Hill where Romulus had founded the city; he would build a temple to Mars, his own ancestor and the avenger of Caesar’s murder; Livy would write the foundation legend more or less as I’ve mentioned it, taking the ancient traditions and putting a pro-Augustan spin on them, emphasising the destiny of Augustus’ reign; and, of course, Virgil would write the Aeneid, the epic Roman response to the Odyssey, telling of Aeneas’ journey across the Mediterranean littered with “prophesies” of Augustus’ triumphant reign.

For example at Cumae in the Bay of Naples, guided by the Sybil, Aeneas descended into the Underworld, where he had a vision of his father prophesying the destiny of Rome. In Virgil’s poem Anchises speaks of Romulus:

under [whose] command glorious Rome will match earth’s power and heaven’s will, and encircle seven hills with a single wall

(Bk VI, 777-807).

He continues:

behold this nation, the Romans that are yours. Here is Caesar and all the seed of Iulus destined to pass under heaven’s spacious sphere. And this in truth is he whom you so often hear promised you, Augustus Caesar, son of a god, who will again establish a golden age in Latium amid fields once ruled by Saturn; he will advance his empire beyond the Garamants and Indians to a land which lies beyond our stars…

Virgil tells that having arrived in Latium, as advised by the river god Tiberinus, Aeneas sought an ally in King Evander of Arcadia. The Arcadians lived inland on a hill, named Pallantium for their divine ancestress Pallas, which was to become the Palatine Hill. Aeneas and his men rowed up river, aided by Tiberinus. After a night and a day of rowing, the settlement of Pallantium hoved into view. When they arrived, Evander was making an offering to Hercules in a grove between the settlement on the hill and the river. The sacrifice was offered in thanks for Hercules’ slaying of Cacus, the monstrous giant who had lived in a deep cave beneath the hill and had repeatedly and brutally attacked the Arcadians and their animals.

Thus, recounting a tale which purports to have taken place some five hundred years before Romulus and Remus washed up in the Lupercal, Virgil is emphasising the Velabrum as the most ancient point of the foundation of the city. As mentioned, it was indeed here that Rome’s pragmatic birth did take place; a trading point of that salt from the marshes close to the mouth of the Tiber. The legendary roots of the city are inextricably linked to its practical origins. Legend is, once again, a way of distilling fact into something more memorable.

Rome’s obsession with its own history, with the genius loci—the spirit of place—can be seen in every corner of the city. “Historical fact” cannot be separated from “legend”; the legend is fact, and belief in these legends has borne results which we still see today. I ride my Vespa past the place where Evander made his sacrifice to Hercules most days, today marked by a small round temple of the late second century BCE which is the subject of the first episode of my podcast. It is a rebuilding, of a rebuilding of a rebuilding, but always more or less, on the same spot right by the river’s first fording by an ancient pontifex, bridge-builder.

Pontifex was a role of such importance in its grappling with the divine and the taming of river gods that the structural and the spiritual would collide. The high priest of Rome would become the Pontifex Maximus. By the time this title was granted to Augustus, centuries after the Tiber was first bridged, it was a ceremonial priestly title, long divorced from the practical business of bridge-building.

“Pontifex Maximus”—an accolade which was so very ancient for Augustus—is still held today. In 380, when Emperor Theodosius issued the Edict of Thessalonica establishing Nicene Christianity as the sole state religion of the Roman Empire, he passed the title of Supreme Pontiff to the leader of Roman Christians, Pope Damasus. The religion of Rome changed, but the title of her high priest remained the same; today, a quarter of the way through the twenty-first century, the incumbent is an elderly gentleman from Argentina. I think that’s just bewilderingly, wonderfully, extraordinary. All aspects of the city’s history— pagan and Christian, ancient and modern—are ultimately rooted in salt, and the tale of a she wolf.

Thanks so much for this Agnes. Lovely writing and, as usual, filled with detail and connections I would not otherwise have made. I love the idea of "the story". Your article reminded me of the work of Joseph Campbell and his "Power of Myth" where he defines Myth as not having to be 'factually true' but, rather, the "truth that we tell ourselves" and around which we organize our values, politics and behaviours. Please keep up the marvelous work.

I remember that very first online talk about salt and the hazy, legendy bits of the founding of Rome! As you so wisely stated that day, let’s begin at the beginning! Brilliant post and always love how you bring all these threads together in such a fascinating narrative!