As the unusually long and hot Italian summer began to break this week, and the storms that normally come after Ferragosto swept across central Italy with unexpected alacrity, we retreated to the verdant hills of Sabina to stay with our classicist chums (I recommend Gideon Nisbet’s excellent translation of Martial, his blog, and Diana Spencer’s splendid book on Varro).

We share an enthusiasm for jaunting in search of the inexhaustible delights of Lazio: abandoned medieval villages long swallowed by forests, arches of ancient aqueducts, and possible Roman villas lurk down every country road. One such site is the defunct quarry on the Monte Lacerone near Cottanello: very much my bag.

The stone that was once quarried here is referred to inaccurately as “marmo” di Cottanello. Marmo (marble) is a term often used generically in Italy to refer to both limestone and marble (and indeed other stones too with a relaxed geological inaccuracy that I’m afraid has always irked me). Along with a vague idea of the formation of oxbow lakes, and the notion that treacherous longshore drift washes English beaches towards France, one of the only things I recall from school geography lessons is that limestone is a sedimentary rock - formed by the accumulation of fossilised debris - and that marble is a metamorphic rock: a transformation of limestone under pressure. Marble is thus denser, heavier, in Rome comes from further away, and is harder to quarry. It is, therefore, more expensive.

The reddish “marmo” di Cottanello is, then, not marble at all but an argillaceous limestone, or a limestone containing an appreciable proportion of clay. Though it polishes beautifully it is far less solid than marble, and as a result in antiquity was deemed not quite bling enough for Rome. The Imperial city, after all, enjoyed flexing her territorial muscles by importing coloured stones from the far reaches of Empire as I’ve mentioned in my previous posts about cipollino marble and porphyry. A striated red limestone from the Sabine Hills was hardly anything to write home about. Thus it was that during the Imperial period the quarries at Cottanello were purely for local use, for example at the nearby villa of the Aurelii Cottae.

Following the slow but inexorable implosion of an Empire addled by bad governance and religious discord, the quarries (like so much else) were abandoned. Smart columns were replaced with fortresses; luxury with subsistence.

It was only in the seventeenth century that Cottonello “marble” once again began to be prized, and this time it was good enough for Rome. In the seventeenth century the erstwhile caput mundi was in the midst of one of the greatest of its many architectural flowerings. The city had been threatened a century before with the protestations of Martin Luther, and the subsequent reverberations of those kings, dukes, and princes who had sought to liberate themselves from the shackles of papal power. The Protestant Reformation soon revealed itself to be rather more than a little local difficulty, and the Roman Church sought a programme of damage limitation.

The Catholic, or Counter, Reformation was born (the choice of term favoured depends on one’s allegiances) and brought artistic austerity. Art was to be a didactic tool and churches were to be clear spaces without distractions focused entirely on the Mass. Bling was out.

A century later, however, that would all change: aided by a spate of military victories and gold flooding into papal coffers from the “New World” by way of the Spanish Crown, the PR machine of the Roman church went all out. A spate of canonisations emphasised spiritual mystery, the focus was on visions and relics, the aim of church architecture was now to wow the faithful. Pilgrims who had walked to Rome on long and treacherous journeys, for most the only journey of their lives, would be presented with an opulence beyond belief: a glimpse of heaven. The Roman Baroque sought to be as un-Protestant as possible. That was the point.

Undoubtedly the great decorative project of the seventeenth century was the interior of St Peter’s Basilica, a replacement for the church which had been built by Constantine over the place of the tomb of Peter. When work on the interior began in earnest in the 1620s the building project had already been underway for over a century. The man who would leave the greatest mark on the interior was Gianlorenzo Bernini, the pioneering superstar of the Roman Baroque. It was under Bernini’s aegis that the master mason Sante Ghetti, familiar with the quarries of Cottanello, was commissioned to carve twenty-four columns (which would become forty-six) of the red stone for the Basilica. These columns were taken from the quarries to the valley of the Tiber by mule before being loaded onto barges and floated along the river to Rome. Before his death, and just shy of his eighty-second birthday, the last project Bernini worked on at St Peter’s was the funerary monument to Alexander VII. A spectacularly theatrical use of a rather awkward doorway sees a winged skeleton suppressed by a heavily billowing cloth while above Alexander is triumphant in prayer, victorious over Death. On either side are columns of the marmo di Cottanello.

The same stone is found at the church which Bernini considered his great masterpiece, and which is one of my absolute favourites (more of which anon), Sant’Andrea al Quirinale. In the exquisite, dizzying, oval space columns of the veined red Cottanello stone frame the high altar, while above St Andrew floats into the gilded heavenly realm of the dome, his passage aided by the obliging bending of the entablature.

Although in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the city of popes advertised its role as the direct heir to the city of emperors, its grand architecture knowingly inspired by antiquity, the geological map of the second Rome was much more domestic. Emperors may have eschewed the charms of the stone of Cottanello but cardinals and popes embraced its value-for-money showiness.

As we explored the long defunct quarry, attractively shaded by woodland that has long reclaimed the site, a single unfinished column emerged from the rock. Like Michelangelo’s Slaves it remains forever frozen in a state of becoming, its redness lurking below an unfinished surface encrusted in lichen and oxidation.

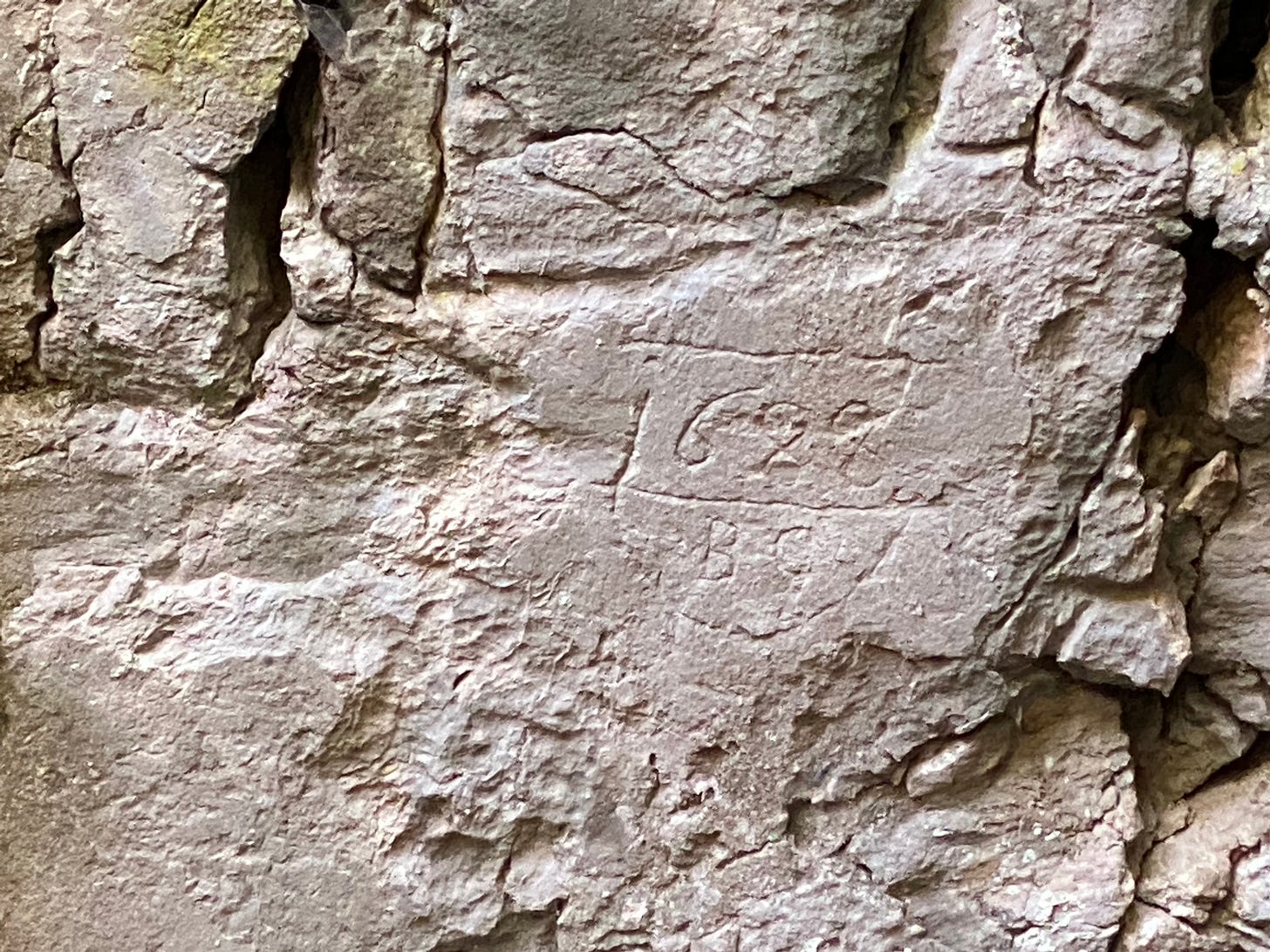

The cliff made by centuries of the sporadic hewing of rock bears a clearly visible inscription. “1688” it reads. Just six years after the death of Bernini it appears that this area of the quarry was once again abandoned, to be reclaimed by nature.

This was so interesting, thanks Agnes! And things being hewn into stone remind me of Spinal Tap and Stonehenge (this is a very good thing).

Very interesting. I'd never heard of this type of 'marble' or the quarry site.