“… [Hannibal] took the Numidians in relays to work at building up the path, so that with great difficulty in three days he managed to get the elephants across, but in a wretched condition from hunger; for the summits of the Alps and the parts near the tops of the passes are all quite treeless and bare owing to the snow lying there continuously both winter and summer, but the slopes half-way up on both sides are grassy and wooded and on the whole inhabitable.”

Polybius, The Histories, Book III, 55.

I’ve spent a considerable amount of time in idle contemplation of Hannibal crossing the Alps. In 218 BCE did an Alpine shepherd look up and, blinking in bewilderment, witness weary and under-nourished elephants negotiating the mountain passes? Or was our putative shepherd perhaps looking the other way, oblivious to the momentous events unfolding behind him? This scenario always reminds me of Bruegel’s glorious painting of the Fall of Icarus, his legs disappearing beneath the waves as everyday life carries on all around regardless.

Two years later, in the heat of early August at Cannae in Puglia, Hannibal defeated the largest Roman army ever assembled. According to Polybius seventy thousand Roman soldiers were killed, if this number is to be believed the second of August of 216 BCE was the bloodiest day in the history of warfare. Today Canne della Battaglia is the name of a motorway service station, which is just the sort of bathos I’m very much here for.

The Roman humiliation was enormous. Twelve years later Publius Cornelius Scipio, scion of the great military dynasty of the Republic, invaded Africa and would eventually triumph at Zama. Hannibal was defeated. Scipio would be awarded the epithet “Africanus” in honour of his conquest. For the first time, Rome’s territories extended to another continent.

According to Pliny the Elder, a century and a half or so later a yellow marble once favoured by Numidian kings and quarried in ancient Simitthus (modern-day Chemtou, Tunisia) was first brought to Rome to decorate the house of Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, consul in 78 BCE and father of the Lepidus who would form the Second Triumvirate with Mark Anthony and Octavian. The quarries of giallo antico were a hundred kilometres north-west of the site of Scipio’s victory over the Carthiginians fought just over a century earlier, a fact surely overlooked by no one.

From the late Republic onwards Numidian yellow would be used with abandon, becoming one of the classic colours of Roman decoration. Its ubiquity in the canon of Roman decoration surely meant that it was recognised by Romans of every stratum of society. As the average Marius wandered past the columns of giallo antico in the Pantheon, for example, he surely knew where it came from. Geographically we can assume his understanding would have been vague—across the sea, somewhere in Africa—but I imagine those columns would have conjured up jingoistic visions of tales told for centuries of the great general Hannibal, and of his elephants, whose ambitions were ultimately thwarted by the might of Rome.

The might of Rome, that “Empire without end” of the Jupiter of Virgil’s imaginings (Aeneid Bk I, 278-9), turned out not to be infinite after all. The Empire ultimately fell, and from its ashes rose the phoenix of the Church. The new Rome advertised her power by repurposing the colours of Roman conquest.

For example the ceiling of the grand hall of Palazzo Colonna vaunts the triumph of the family’s greatest scion, Marcantonio (a Roman name if ever there was one), admiral of the papal fleet and instrumental in the triumph over the Ottoman Empire at Lepanto in 1571. That ceiling is supported by vast columns not of Numidian yellow but faced in Sienese yellow marble (one can assume had they been unable to find intact columns of giallo antico on such a scale), however the evocation of the colours of Roman triumph is unmistakeable.

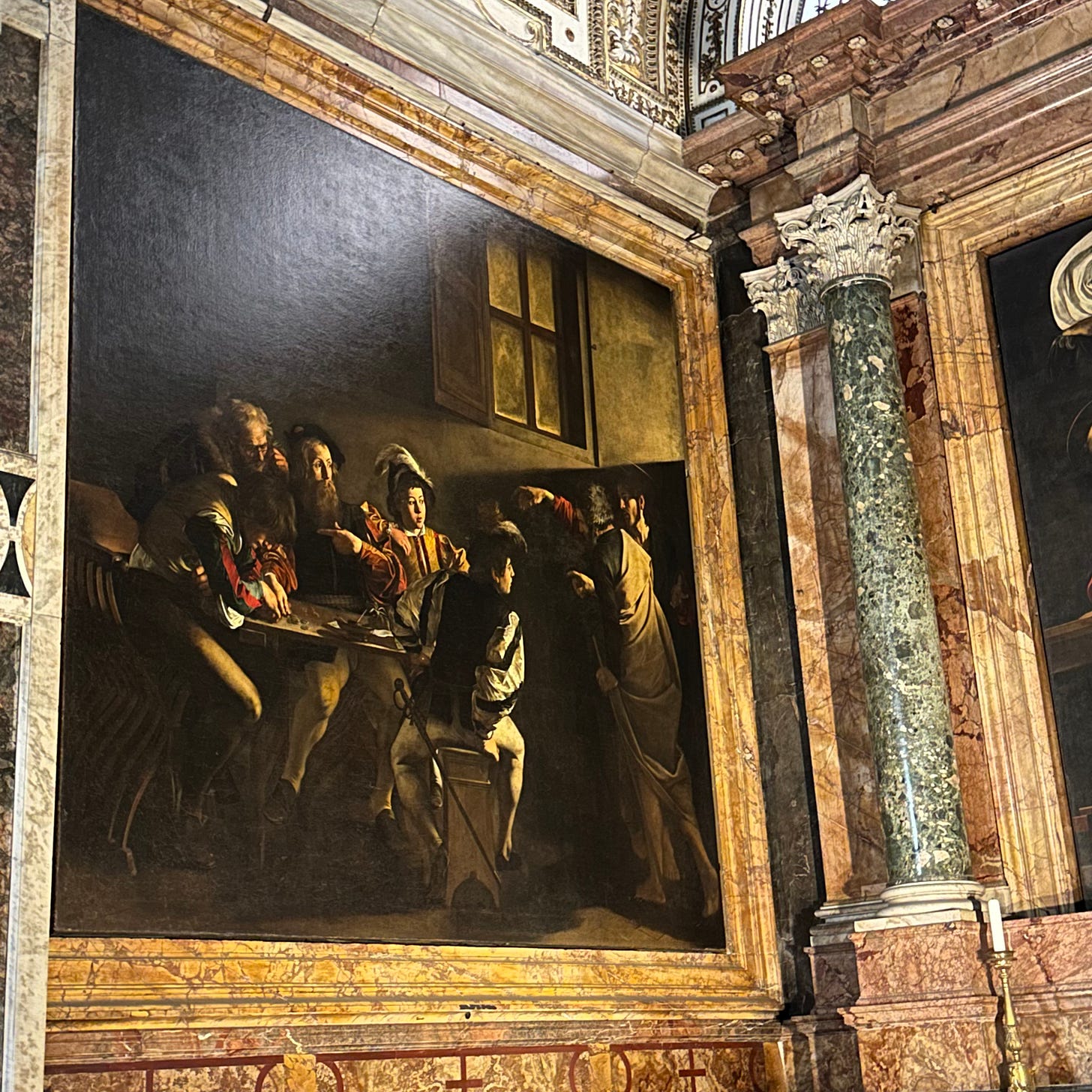

We also see directly repurposed Numidian yellow at every turn in the papal city: for example above in the Museo Borghese, and below at San Luigi dei Francesi.

Here an Irish Dominican monk strides across a floor peppered with giallo antico at San Clemente in a dizzying palimpsest of centuries.

Every time I spot a piece I think of quarries in Tunisia (how many squashed people?); of boats sailing across the Mediterranean (how many languish at the bottom of the sea?); and of Hannibal and his weary elephants crossing the Alps, and whether a shepherd did indeed witness this extraordinary spectacle in 218 BCE, and if so what on earth he must have made of it.

I particularly enjoyed this piece and will now savour every yellow marble column, floor etc I come across in Rome.

Agnes love your “idle contemplations”, wherever you are in the Roman world. You see so many wonderful stories wherever your look.

Picones