This spring’s big ticket in Rome is the Caravaggio exhibition at Palazzo Barberini which opened in March and will run to early July. It is rapidly selling out and is a glorious gallop through twenty-four paintings, including a couple of less than certain attributions, but there is not a dud amongst them. A dizzying battery of beauty crammed into Palazzo Barberini’s (too?) small exhibition space. With the loans in Rome for the show, and those paintings already in churches and museums across the city, some two-thirds of Caravaggio’s entire oeuvre is presently in town. I have become more than a little carried away thinking about the dense show so this is Part 1. Part 2 will be coming next week.

Before beginning, I must admit I find such exhibitions provoke certain (possibly bah humbug-ish) misgivings: permanent collections including the exquisite Palazzo Barberini are empty for most of the year, even as the exhibition queues gather below its great Salone with Pietro da Cortona’s glorious and vast ceiling; the exhibition could undoubtedly have been better displayed in a larger space; stripping galleries around the world of one or more of their star pieces is unfair on their visitors; moving paintings around the world takes no small toll on the health of the paintings. Despite understanding that it is a complicated business, I could also be a little grumpy (and I’m certainly not alone) about the lighting but, my innate cheerfulness returning, I would say the paintings are all in town now. If you can I would urge you to go and see them!

In 1571, probably on the 29th September—Michelmas, the Feast of the Archangels, hence his name—Michelangelo Merisi was born in Milan. His father, Fermo, worked in the city as an administrator in the household of the Marquis of Caravaggio. In 1576 the family fled plague-ravaged Milan for the town of Caravaggio, the epithet by which the then infant Michelangelo Merisi would become celebrated beyond imagining. The family’s efforts were, however, in vain and the young Michelangelo’s father, uncle and grandfather all died of plague at Caravaggio the following year.

Caravaggio’s childhood, then, played out under a brooding cloud of plague, famine, and desolation and by the time he was eighteen his mother had died too and he was an orphan. For Charles Borromeo, then the fire and brimstone Archbishop of Milan, the plague had been sent to Milan as divine punishment. It is difficult to see how a child growing up in such an environment could fail to be enormously affected by it.

Already at the age of twelve Caravaggio was apprenticed in Milan to the painter Simone Peterzano, who claimed to have trained under Titian. After his apprenticeship and following the death of his mother, Caravaggio sold a piece of land he had inherited which may have funded travels in Lombardy, perhaps even as far as Venice where he would surely have seen the work of Giorgione, as well as Titian and Tintoretto.

The Palazzo Barberini show begins with what happened next. Caravaggio was in his early twenties when he arrived in Rome. The city was then home to perhaps a hundred thousand people, densely packed into the shadowy, narrow vicoli of the Field of Mars and Trastevere. The vast majority of the population occupied a corner of what had once been the imperial capital; sheep grazed amid the ruins of its long-abandoned civic hub in the Forum; and the centre of gravity of the Caput Mundi had shifted to the Vatican. For, despite its massively diminished size, the presence of the Church made Rome still a major capital. Far more significant than its population suggested, it attracted princes and paupers from across Europe and in Jubilee years the pilgrim population was larger than that of the city’s residents.

Upon arriving in Rome from Lombardy, Caravaggio was initially a guest of Monsignor Pandolfo Pucci of Recanati in the Marche. Pucci appears to have lived up to the marchigiana stereotype of tightness, and was known as Monsignor Insalata for the poor quality of the food in his household.

The Boy Peeling Fruit, here on loan from the Royal Collection at Hampton Court, is believed to be one of Caravaggio’s earliest Roman works and has been identified with a painting of the same subject mentioned by his early biographer Giulio Mancini as being painted while he was staying with Pucci. There is, however, no provenance of this painting before 1688 (the year of the Glorious Revolution, but that’s another story) when it was almost a century old and is recorded as being by “Michael Angelo” [Merisi] in the collection of King James II of England and VII of Scotland. As well as this provenance, and despite the painting’s poor condition, the quality of the fruit in the foreground has been seen as enough to justify the attribution to Caravaggio. The small fruit being peeled has been identified as a Neapolitan limoncello, the juice of which was considered beneficial to digestive health, giving the painting moral overtones of temperance and hygiene.

Caravaggio soon fled the temperance, citric acid, and soggy salad of Monsignor Pucci and found lodgings with a certain Tarquinio—an innkeeper and brothel owner—before moving through several artists’ studios (one mentioned belonged to a Sicilian referred only as Lorenzo). He was immersed in the demi monde of the Caput Mundi: those shadowy vicoli populated by people who would become the models for his paintings and provide the extraordinary immediacy of so many gazes undimmed by centuries.

Subsequently—still in the nineties of the sixteenth century—Caravaggio was employed for eight months by the extremely prolific workshop of Giuseppe Cesari (later known as the Cavaliere d’Arpino) before they appear to have abruptly fallen out. The future Cavaliere was only three years older but already master of a prosperous studio. Another of Caravaggio’s biographers, Giovanni Pietro Bellori, said that in the studio Cesari “had him paint flowers and fruit, which he imitated so well that from then on they began to attain that greater beauty that we love today.”

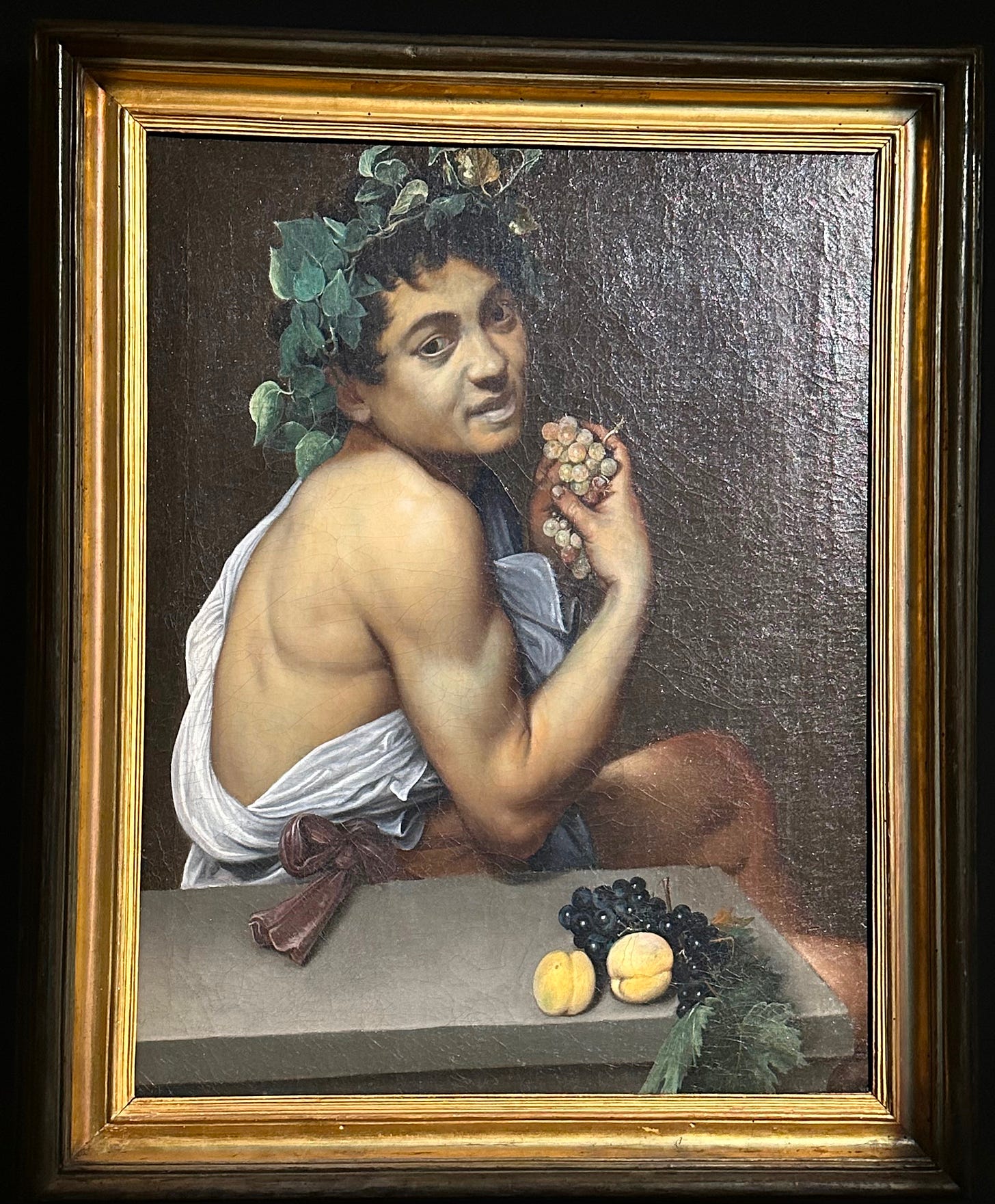

During this period Caravaggio is believed to have been hospitalised at the Ospedale della Consolazione adjacent to the Forum, his life swinging in the balance. His self portrait as the Sick Bacchus was painted using a mirror during his recuperation. First mentioned in 1607 in the inventory of works sequestered by Paul V from the Cavaliere d’Arpino to boost the collection of his nephew Scipione, it usually still hangs in the Borghese Gallery, from where it is here on loan. The sallow pallor of the god of wine, leering with grey lips, is quite at odds with traditional cheery representations. Bacchus grasps the grapes in hands with grubby fingernails as he stares out at us, and the leaves both of his crown and on the table in front of him are cut off abruptly by the frame, as if the scene continues beyond the scope of the painting. This choice of framing, as if the scene were an arbitrary snapshot, is a characteristic of Caravaggio’s painting (and Baroque painting more widely); a device which emphasises the fleeting nature of the moment captured.

Despite misfortunes such as this dangerous bout of ill health, and the foul temper which saw the abrupt termination of his employment by the prolific and canny Cavaliere d’Arpino, Caravaggio made a number of important connections in Roman society at this time. Through the successful painter Prospero Orsi, with whom he also lodged for a period, Caravaggio met Costantino Spada, a well-connected dealer, and at the end of the 1590s was introduced to Francesco Maria del Monte and the Genoese banker Ottavio Costa, both of whom would become important patrons.

It was for Costa that he painted the devotional image of St Francis in Ecstasy, the earliest religious scene in the exhibition, on loan from Hartford, Connecticut. St Francis of Assisi is shown supported by an angel having fallen into a faint upon receiving the stigmata. The only of Francis’ wounds visible is that of the spear of Longinus on his chest. The representation of Francis swooning in the arms of the angel is unusual, focused on Francis’ interior experience—his eyes, half open, are seeing something we don’t—rather than showing us his vision of the crucifixion amid seraphim.

The inclusion of the angel perhaps alludes to Christ’s agony in the garden which in the Gospel of Luke refers to the presence of a consoling angel. Also unusual is the inclusion of Brother Leo, confessor of Francis, lurking in the shadows to the left of the scene.

Around the same time the disputed Narcissus is believed to have been painted, here catalogued as an attribution rather than an autographed work. Narcissus gazes, besotted by his own reflection, into the pool in which he will drown. It was a mythological theme favoured by Dante and Petrarch and prevalent in the milieu of Caravaggio’s new patrons, as well as being a theme described by his friend the poet Giambattista Marino. As Leon Battista Alberti said in his fifteenth century treatise On Painting:

the inventor of painting ... was Narcissus ... What is painting but the act of embracing by means of art the surface of the pool?

Francesco Maria del Monte, Caravaggio’s most important early patron, owned three paintings from this first Roman period: Il Concerto (The Musicians), I Bari (The Card Sharps), and the Buona Ventura (the Fortune Teller) all of which are displayed here: respectively they have travelled from New York City, Fort Worth and—rather closer to home—the picture gallery of the Capitoline Museums.

Cardinal del Monte was an extremely interesting figure. He was an enthusiastic and sophisticated patron of the arts—protector of Galileo, collector of antiquities, owner of a vast library, host of cultural soirées—and was close to the Medici in whose Roman palace, Palazzo Madama (now the Italian Senate House), he lived. Circa 1595/6, when the painter was twenty-four years old, Caravaggio entered the household of the Cardinal, presumably living in one of the servants’ rooms on the top floors. The cardinal had an extensive collection of art including five Titians (perhaps optimistically claimed to all be originals) and the first century glass Portland Vase, now in the British Museum.

The first painting by Caravaggio to be owned by Cardinal del Monte was the Buona Ventura, usually translated into English as the Fortune Teller. It is a genre scene uncommon in Italy, but directly rooted in Flemish tradition which we can see trickling down to Rome via Caravaggio’s Lombardic origins (and, perhaps, his Venetian foray). The subject is taken directly from popular theatre of the time, the dappled light on the otherwise empty background giving the sense of a fleeting moment captured.

A fresh-faced young aristocrat is decked out in his finery and is oblivious as a woman, under the pretence of reading his palm, cheerfully and skilfully relieves him of a ring. The bright colours, and the naturalism in the depiction of human foibles was different to anything in Rome at the time.

I Bari is another genre scene, probably predating the Buona Ventura, showing a wealthy and naïve boy in the act of being duped. This time time the unworldly victim—rosy-cheeked with crisp lace cuffs and an opulent dark velvet doublet—is playing zarro (a game of Persian origin which had been outlawed by Francesco Sforza, Duke of Milan, decades earlier as being socially dangerous) with a young man of a similar age.

He is so intent on his cards that he is oblivious to an older man peering over his shoulder with almost comically wide-eyed concentration. His hand housed in a ragged glove indicating a distinct social dichotomy, the older man indicates to his accomplice while the young cheat has his hand behind his back ready to pluck one of the spare cards he has in his belt. Also hanging from his belt is a dagger, leaving us in no doubt that this isn’t merely a game.

Both of these scenes were probably painted by Caravaggio as inventory following his swift exit from the Cavaliere d’Arpino’s studio and bought by del Monte. The third from his collection was, however, commissioned by the cardinal. Il Concerto (The Musicians) is an allegorical allusion to the concerts that Del Monte sponsored at Palazzo Madama.

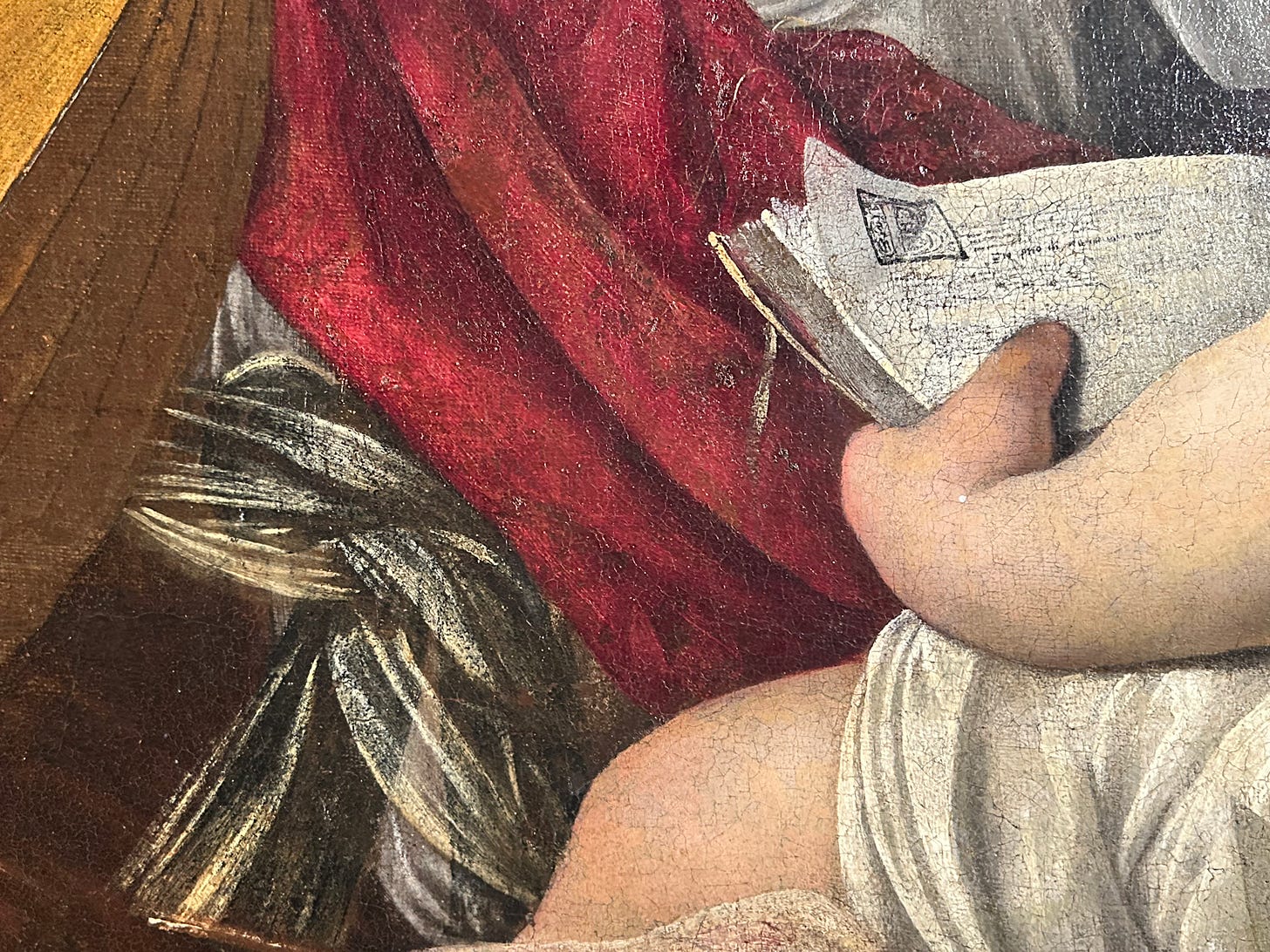

Sheet music by the contemporary Neapolitan composer Pompeo Stabile is visible in the foreground. Giovanni Baglione, with whom Caravaggio would have an extremely acrimonious relationship but whose biography of the younger artist is written with the generosity of distance years after Caravaggio’s death, wrote that he

dipinse per il Cardinale una musica di alcuni giovani ritratti dal naturale, assai bene…

[for the Cardinal he painted from life some young men playing music, extremely well…]

Cardinal del Monte would soon be the conduit for Caravaggio’s first church commission, a distinct shift in gear, when he put him in contact with the Cointerel family who were commissioning paintings showing scenes from the life of St Matthew for the family chapel at the church of San Luigi dei Francesi adjacent to Palazzo Madama.

The success of this commission swiftly led to another major church commission, this time from Tiberio Cerasi, a lawyer and treasurer of the Apostolic Camera, at Santa Maria del Popolo. The Cerasi chapel was still under construction when Caravaggio was commissioned to paint two panels: the martyrdom of Peter and the conversion of Paul.

According to Baglione’s biography of Caravaggio the first versions were rejected, perhaps because the perspective of the scenes didn’t work well in the tight space when the chapel completed, and instead entered the collection of Cardinal Sannesio. The Cerasi commissions follow a torturous path not uncommon in Caravaggio’s economically unstable career.

Though the contract signed in September of 1600 was for four hundred scudi, payment would only be made in November of 1601 (by which time Tiberio Cerasi had died) and would be a hundred scudi short. The first version of the Martyrdom of St Peter is long since lost, however the conversion of Saul is usually in the private Odescalchi collection. It is much busier than the second version which is still in situ at Santa Maria del Popolo. Both versions narrate the story of Saul of Tarsus, persecutor of the Christians, at the moment of his conversion on the road to Damascus told in the Acts of the Apostles.

The most common version of the scripture tells that Saul was blinded by a dazzling light and that he heard the voice of Christ and that his companions heard the voice but saw no light. In Caravaggio’s first version of the painting we see a very physical representation of Christ—anything but ethereal—supported by an angel in the top right-hand corner of the painting as Saul falls to the ground, his hands clutching his face and covering his eyes.

Above him a grizzled soldier clasping a spear and a shield looks unseeingly in the direction of the figure of Christ and the startled horse bucks adding to the claustrophobic density of the action barely contained by the frame.

Despite erratic moods, which saw him repeatedly arrested for affray, by the time he came to the attention of Tiberio Cerasi Caravaggio had become ever more popular among grand patrons. Some time around 1595 he is believed to have painted the first portrait of Maffeo Barberini who would become Pope Urban VIII, and for whom the palace which houses this show would be built. Long ascribed to Scipione Pulzone, its attribution to Caravaggio is certainly not universally accepted: it is here catalogued as an attribution. We see the future Pope in his late twenties and wearing the robes of an apostolic protonotary, a significant position in the Roman Curia which had been ceded to Maffeo by his uncle Francesco in a fine bit of sixteenth century nepotism. Now in the private Corsini collection in Florence (where it found its way following the mid-nineteenth century marriage of Anna Barberini Colonna to Tommaso Corsini) the young prelate is shown with the billowing robes of his rapidly rising career.

This is shown alongside a second portrait of Maffeo, identified as the work of Caravaggio by Roberto Longhi in 1963 and also here on loan from a private collection (though the Palazzo Barberini is presently angling to buy it for the nation). Maffeo is about thirty years old here and it was perhaps commissioned following his appointment to the Camera Apostolica in March of 1597. He certainly hadn’t let the grass grow under his feet.

Maffeo’s bright eyes glance away from the viewer, and the dynamic gesture of his right hand emerging from the voluminous white sleeve—just a hint of the red lining of his dark robe visible at the top—almost breaches the frame.

In his left hand Maffeo holds a letter, perhaps that of his recent appointment to the papal treasury, a fundamental step on the path to the cardinalate. We see here the beginning of the dramatic use of shadow which would be so characteristic of Caravaggio’s career.

To be continued…

You got such great photos! I was there yesterday afternoon and it was packed! Almost like being on an ATAC bus, practically shoulder to shoulder! Could hardly admire the paintings much less get a good photo. But still, such a treat to have 25 of 50 of his paintings in one place is such a luxury. Just being in the presence of his deep reds and draped fabric that seem real is extraordinary.

Thanks for that, as always, fascinating. How bad will it get to get tickets -- we arrive right on Easter weekend. Wait till May -- middle of the week? lunch time?