Hot springs and Hopefulness: the profound humanity of the bronzes of the sanctuary at San Casciano

December 2019 was the most recent of my visits to San Casciano dei Bagni. I was with a couple of friends and we parked by the almost deserted Roman vasconi on a crisp Tuesday morning, changed in the car, and bathed in one of the pools fed by natural hot springs before repairing to the town at the top of the hill for pasta and truffles, gently reeking of sulphur. Etruscans, terme, and truffles was—we decided along the way— the theme of that jaunt and it was excellent. A few months later the world stopped in the face of a global pandemic. It all feels like an awfully long time ago.

Last month I went to the exhibition at the Palazzo del Quirinale of the two dozen bronzes, and some of the over five thousand coins in bronze, silver and gold, discovered a stone’s throw from those waters where we wallowed.

An auspicious place to display such finds and once the summer palace of the Popes, the Quirinal Palace was modified to become Napoleon’s Rome residence (though in fact he never came to the city which was to have been his second capital). Following the definitive fall of papal rule in Rome in 1870 it became the seat of the kings of Italy until the referendum of 1946 decreed Italy a Republic. It has since been the seat of the President of the Italian Republic, an office held since 2015 by Sergio Mattarella.

It is also where—in 2001, aged twenty-three—I was sent by a language school to teach English to civil servants. They included two delightful chaps who travelled everywhere with the then President, Carlo Azeglio Ciampi, of whom they always spoke with great fondness. On one occasion they kindly and enthusiastically walked me through the extensive palace gardens as I tried, earnestly, to earn my pay by attempting to engage them in conversations employing the present perfect continuous; on another they took me to send my mother’s birthday present from the internal post office.

The exhibition (now extended until 22 December 2023; free but booking required) offers a temporary home for the discoveries which will be eventually housed in a museum space in the town of San Casciano, overlooking the site where they languished, unseen for a couple of millennia. These are the most important collection of bronzes discovered in the Mediterranean since the Riace Warriors were found in Calabria in 1972. They were also given the honour of being displayed first at the Quirinal Palace before being rehoused in the Archeological Museum at Reggio Calabria.

Not far from Siena, San Casciano dei Bagni has one of the largest sources of hot spring water in Europe: 42 springs with an average temperature of 40C (104F) gush forth 5.5 million litres (about 1.5 million gallons) per day. These hot springs—like those of nearby Chianciano, Rapolano, Bagno Vignoni, and Saturnia to name just a few— are the product of long distant volcanic activity on the Italian peninsula. The liminal nature of such places, on the cusp of the earthly and the underworld, have long been imbued with spiritual significance, not least for their curative properties.

Tradition says that it was Lars Porsenna who established the baths around Chiusi, including those at San Casciano. Porsenna was the lucomone (the highest office of the Etruscan city states) of the city of Chiusi, perhaps most famous for his attempt to defend Tarquinius Superbus, the last king of Rome, when the last of the Tarquins was overthrown by the nascent Roman Republic shortly before 500 BCE.

Largely concentrated between the Tiber and the Arno, the area occupied by the Etruscans includes areas of the modern day regions of Lazio & Tuscany. The Romans called them the Tusci (from which Toscana, or Tuscany) or Etrusci, (probably in origin an Umbrian term) from which Etruria becomes the term used for the area they occupied.

There are conflicting theories about where the origins of the Etruscans lay: Herodotus claimed them to have been a people indigenous to Lydia in Asia Minor, from where he claimed they had fled famine and a tyrannical ruler and settled in the west of central Italy, where the land was fertile and natural resources abundant.

Another theory was put forward by Dionysius of Halicarnassus, writing in the first century BCE. He claimed that the Etruscans were an autochthonous people, native to central Italy, who had come into contact early with the eastern Mediterranean reflected in their culture. This theory was one which would be espoused during the Fascist period, which very much didn’t welcome the idea of an immigrant civilisation.

Either way Etruscan culture, and art, can be seen as indebted to the Greek and Phoenician worlds with which they traded. It was the Etruscans who served as the conduit through which elements of the Greek world which we now think of as inescapably Roman were introduced to the Italian peninsula: without the Etruscans the Romans would have neither had wine nor gladiatorial combat to pick two notable examples. Another Greek import to Etruria was the perfecting of archaic techniques of casting statues in bronze using the lost wax method, seen in unprecedented quantities and quality in the finds of San Casciano.

Etruscan trade with the eastern Mediterranean was born of the abundance of natural resources on the island of Elba and the area directly opposite on the mainland known as the Colline Metallifere, the “Metal-bearing Hills”. Bronze is an alloy of copper and tin, and both were mined in Etruria (though it appears that in later periods the Etruscan need for tin was augmented by imports first from Iberia and, intriguingly, also from Cornwall).

Such was the Etruscan dominance of the west coast of central Italy that the civilization of canny merchants gives its name to the sea: the Attic Greeks called the Etruscans the Tyrrhenoi (a term used for various non-Greek peoples, not all Tyrrhenoi were Etruscan), “their” sea became the Tyrrhenian. Despite the subsequent centuries of Roman domination of the Mediterranean the name has stuck.

The Roman domination of the Italian peninsula would see Etruria subsumed into the Roman world, and Etruscan towns were destroyed and rebuilt. However there was still a great interest in the late Republican and Early Imperial periods, and there remained a certain kudos in laying claim to Etruscan ancestry: Augustus’ great friend, and the patron of Virgil, Mycaenas (whose name is synonymous with a patron of the arts in Italian, mecenate) came from Arezzo and boasted of his noble Etruscan ancestry; the first wife of emperor number four, Claudius, was Plautia Urgulanilla, whose family claimed Etruscan lineage. Claudius was himself enthusiastically interested in Etruscan culture and language: he wrote a long-lost treatise in twenty volumes on Etruscan history, and is said to have been able to read the language.

Claudius’ books would be destroyed as Rome subsequently sought to eliminate traces of the troublesome impediment to their claims to primacy and supremacy on the Italian peninsula, but awkward facts remain: Livy tells us that the last three of the seven kings of Rome—Tarquinius Priscus, Servius Tullius, and Tarquinius Superbus—were Etruscan; it was during the rule of Etruscan kings that the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus was built, and the valley of the Forum drained. The Etruscans were inextricably interwoven with Rome’s fortunes.

The later Imperial antipathy towards Etruscan culture which saw Claudius’ history obliterated saw also the destruction of Etruscan places, some ideological, some merely pragmatic as towns and cities were rebuilt. Such information as we have of Etruscans, therefore, comes from artefacts, not documentary evidence, and is especially rich in the necropoli of Etruscan towns. The Romans drew the line at interfering with the dead. Too much like bad karma.

Unusually the discoveries at San Casciano come not from a funerary context but a religious one. The sacred and health-giving nature of the springs segued from Etruscan into Roman culture; this was a place too deeply rooted in local culture to be shifted by the change in occupation.

This travertine altar, on display at the exhibition, was found during the first archeological investigations at the site in 1585. It dates to the late second century, when the Etruscan language was a distant memory and Roman domination extended not just across central Italy, as in the first forays into Etruria, but from Scotland to Sudan and the Atlantic to Iraq.

“for the healing of our Caius and Pomponia and their children, [this is] sacred to Aesclepius and Hygeia. The freedwoman Ephestas placed this to give thanks for prayers answered freely and well-deserved.”

P(ro) s(alute) / Cai et Pomp[o] / niae n(ostrorum) libero[ru] / m[q]ue eor[um], / Aesculapio / et Hygiae sacr(um). / Ephaestas lib(erta) / v(otum) l(ibens) m(erito) s(olvit).

These are Roman names, and deities Romanised from the Greek world, in a site of ancient Etruscan significance. Rome is nothing if not a melting pot of Mediterranean cultures.

And so—as Etruria faded, subsumed into the ever-expanding behemoth of Rome—these springs would continue to be used. Their health-giving properties and spiritual importance were given a Roman accent, a continued significance ensured by their proximity to both Rome and the ancient via Cassia, now the SS2, which from the third century connected Rome with the once great Etruscan city of Clusium (modern Chiusi).

Though legend tells of a foundation dating to Porsenna, the finds indicate this part of the religious/bathing complex was definitely active between the third century BCE and the fifth century CE when it was abandoned and deliberately buried, but not destroyed. It is this burial which led the statues and coins to be in such a fine state of preservation rather than being melted down for their metal. Although by the time the Roman empire definitively fell it was a Christian empire, and pagan votive offerings and objects of veneration irrelevant, such was the atavistic pull of the ancient spiritual importance of the springs of San Casciano that the offerings were to be left alone. Regardless of one’s religious beliefs it would, one presumes, have been tempting fate to interfere with them.

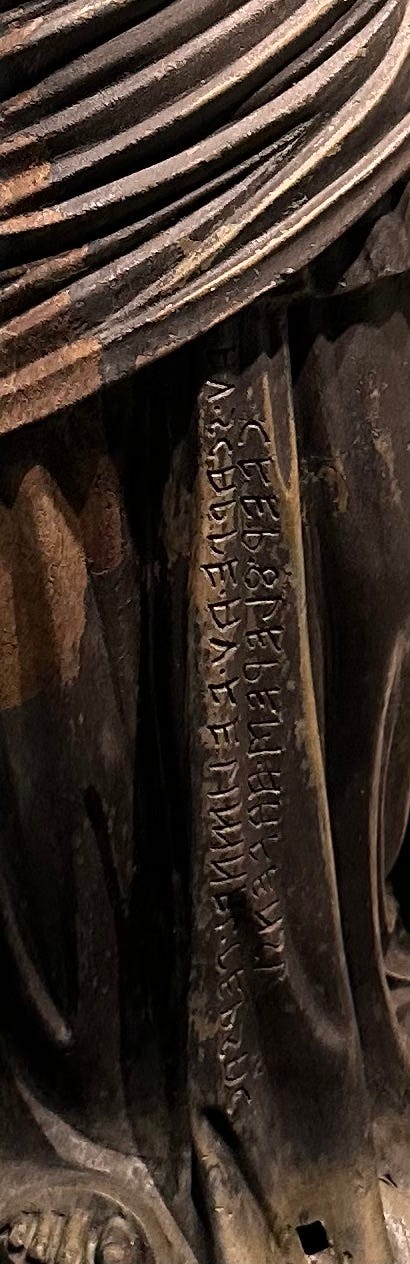

One of the earliest large statues dates to the second century BCE and shows a woman with a patera, a sacred dish for religious offerings. A snake is coiled around her left forearm. The vertical inscription (in Etruscan) reads:

Aule Scarpe, son of Aule and of a Velimnei, (donated this) as something sacred to the Numen of the Fountain

A numen is a sacred force usually identified with a natural place, in this case the woman is the goddess of the spring.

Next to her is an early first century CE statue, perhaps a metre tall, of a young man dating to the early Roman period of the site.

It was perhaps the statue I found most moving, a young man visibly racked by illness, about which presumably nothing was to be done. His hands are open in the gesture of the orans—a person in prayer, a gesture still used today by priests during Catholic Masses. His spindly arms and legs, and concave chest belie his sickness and his expression is one of stoic, but heartbreakingly hopeful, calm. It’s just too moving for words, timeless in its humanity.

In the next room a younger, and apparently rather healthier, boy from the previous century (the first century BC, during the early part of which the sanctuary became Roman) wears a toga indicating his status (something, despite his nudity, we can assume also for the previous young man given the quality of the statue with which his family sought his recovery with such devastating faith).

The elegant, delicate, folds of his toga show the assimilation into (by now) Roman Etruria of the refined Greek techniques of bronze casting.

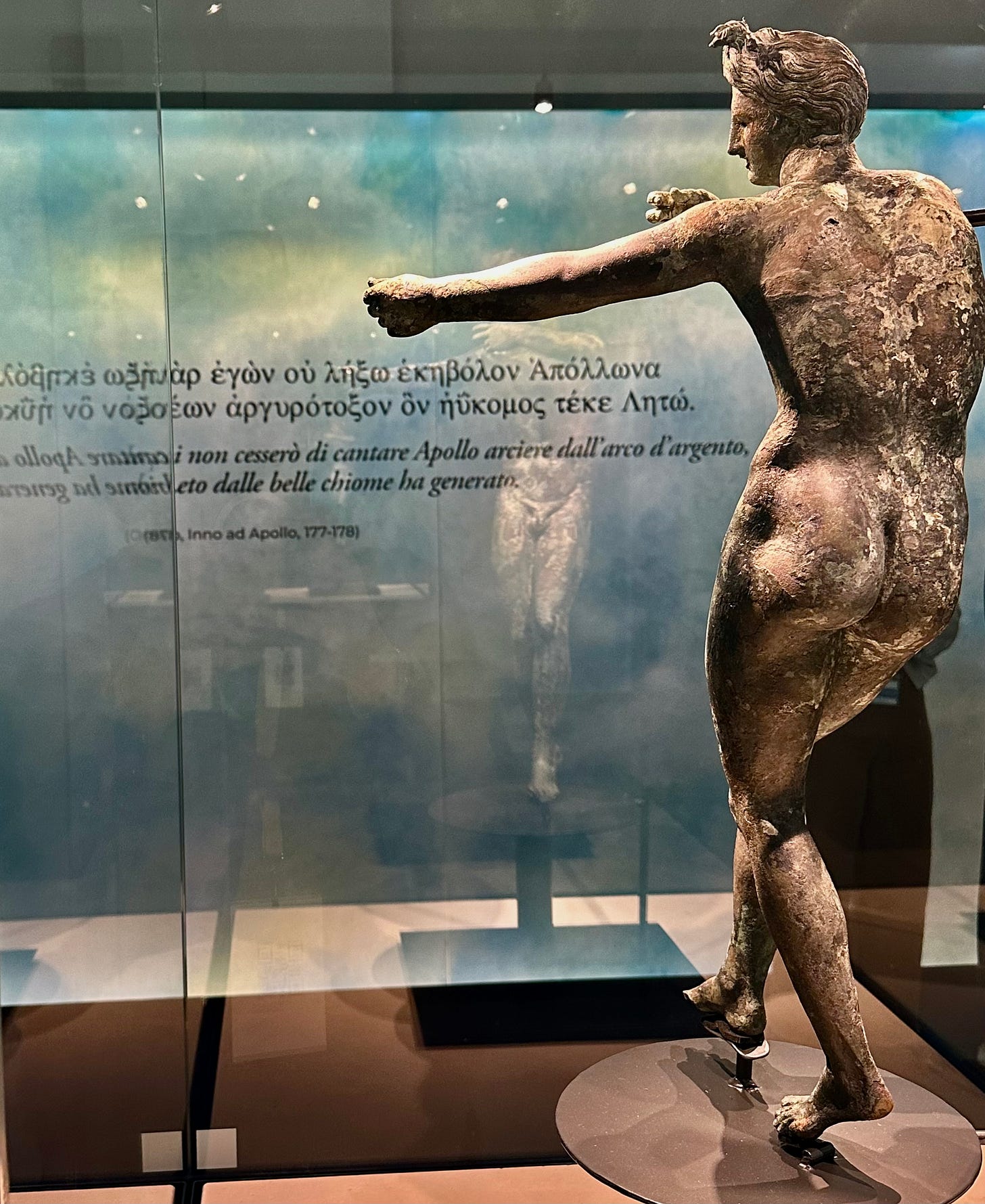

Here we see not a mortal, but a god. A bronze statue of Apollo dating to the second century BCE. Apollo is once again a reminder of the fertile cross-pollination and permeability of ancient Mediterranean civilisations: a Greek deity, adopted on the Italian peninsula by first the Etruscans and then the Romans.

Apollo is shown as the archer: son of Leto and twin of Artemis, born on the island of Delos in the Cyclades.

The quotation in the background is from the Homeric hymn to Apollo:

And I will never cease to praise far-shooting Apollo, god of the silver bow, whom rich-haired Leto bore

As well as being god of the hunt, Apollo, who’s a multi-tasking sort of chap, is also associated with medicine. He is the father of Asclepius and the grandfather of Hygeia, both cited in the Roman era altar we mentioned at the beginning.

Resting on Apollo’s arms, buried in the mud for nigh on 22 centuries, were objects displayed here which allude to his medical role.

This plaque from the second century BCE displays (with great accuracy) internal organs: throat, lungs, heart, stomach, intestines

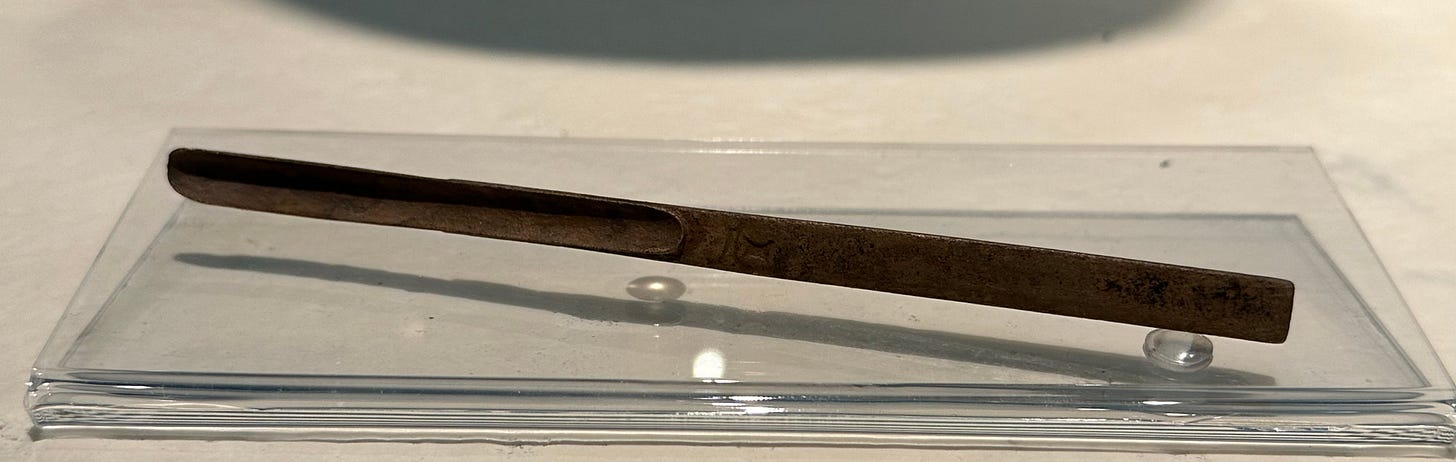

This surgical gouge also of the second century BCE is uncannily similar to instruments used by orthopaedic surgeons to contour bone in modern hospitals.

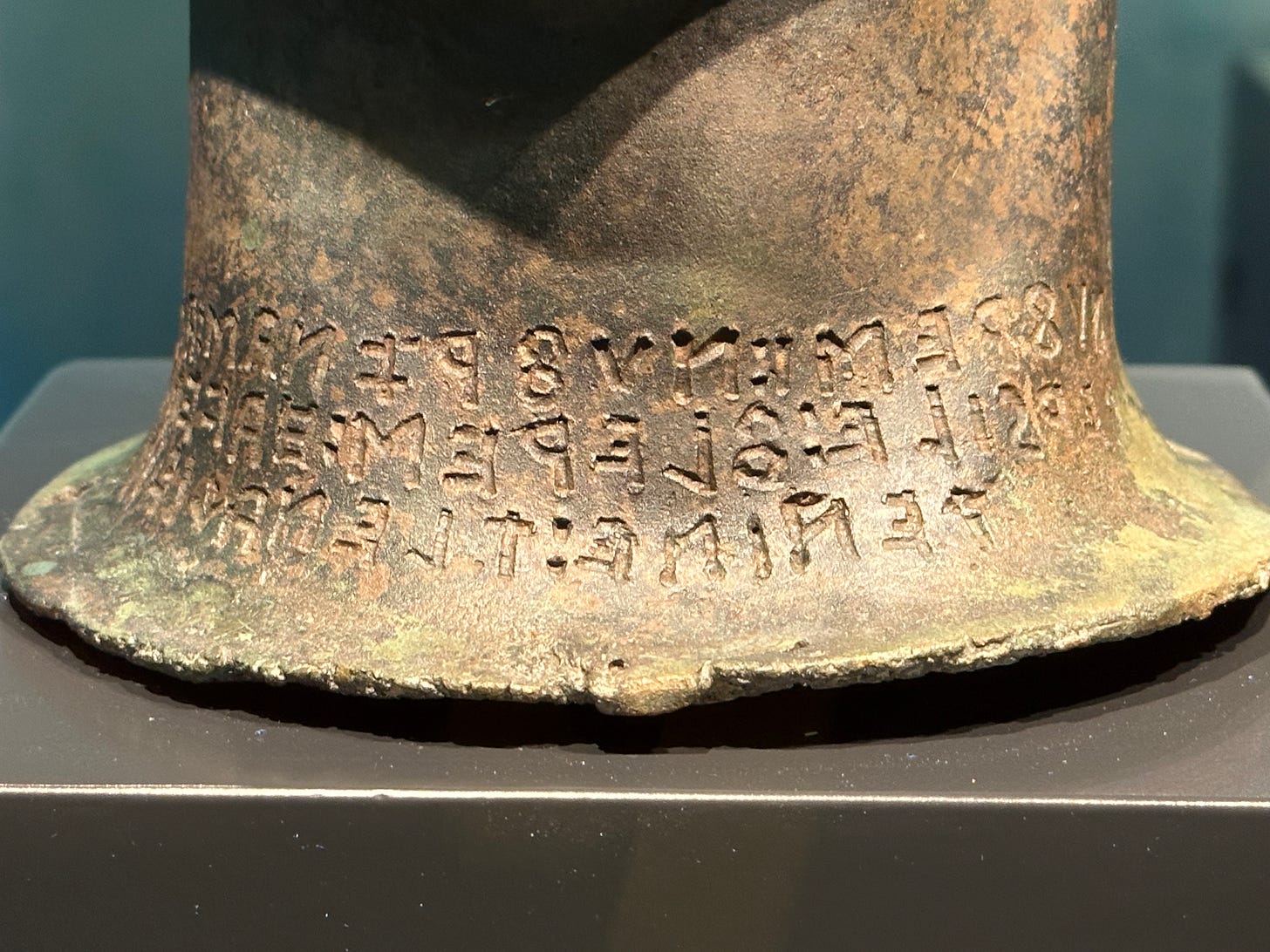

This first century BCE plate shows organs, but also bears a portrait and an inscription telling us of the fellow who sought help from Apollo.

Atimetus, administrator of Sulpicia Triaria, to Fortuna has discharged the vow freely, as is deserved

In the next room we find a portrait of a man from the first century BC, on the cusp of the Romanising of the site, with an inscription in Etruscan on his neck.

On behalf of Nufre, of the Nufrzna family, son of Ar(nth), the Perugian, to the Deity of the Fountain, is placed, for (a vow) to be dissolved

In the same cabinet is a head of a woman, perhaps from the late Augustan period—the early 1st century AD— judging by the hairstyle.

Once again it is recognisably a portrait: we are in no doubt that these are real people. She is a woman of a certain age, full of face, the hint of a smile on her lips, and the downturned wrinkles by the side of her mouth that any woman over forty recognises with dismay, and with defined eyebrows.

She has empty hollows where her eyes should be and holes in her earlobes indicating other materials once completed the portrait: perhaps ivory eyes and gold earrings.

Among the numerous smaller pieces there are body parts, a uterus, a curiously pointy penis, breasts, eyes, and ears. A selection of the five thousand or so coins of various periods found in the various levels of mud is also on display.

A reminder that the yearning to throw coins into fountains and wells is a deeply atavistic impulse, something I always think as I battle through the selfie-takers at the Trevi Fountain. Some things are just profoundly, timelessly, human.

Such a fantastic article! As always, your talent for weaving together multiple sources into a fascinating narrative is spot-on! Also, the photos are EXCELLENT for those unable to see the exhibition in person. You brought attention to details on the pieces that I missed when we attended the exhibition in September! 🙌

This exhibit is sold out for my dates next week. I will definitely try to catch it on another visit, when it is at San Casciano. Great excuse to go back to this area!