March's Postcard from Rome

A couple of thoughts on Roman Neorealism, and details of a themed jaunt with Rachel Roddy

When I was perhaps twelve I remember being taken by my father to see the 1948 masterpiece of Italian Neorealism Ladri di Biciclette—Bicycle Thieves—at the National Film Theatre on the South Bank of the Thames. It was, as my younger brother bemoaned, one of those films you had to read.

Ladri di Biciclette is a tale of unrelenting and exhausting misfortune told by non-professional actors and using real locations, which stand in sharp contrast to the grandeur and romance of the city’s monuments. The protagonist, Antonio, and his family live in newly-built public housing at Val Melaina, then on the outskirts of the city, and when he comes into Rome for work he enters, entirely geographically coherently, by the via Nomentana at Porta Pia; we see the via del Traforo, the late nineteenth century tunnel below the Quirinal, but not the Trevi Fountain barely two minutes away.

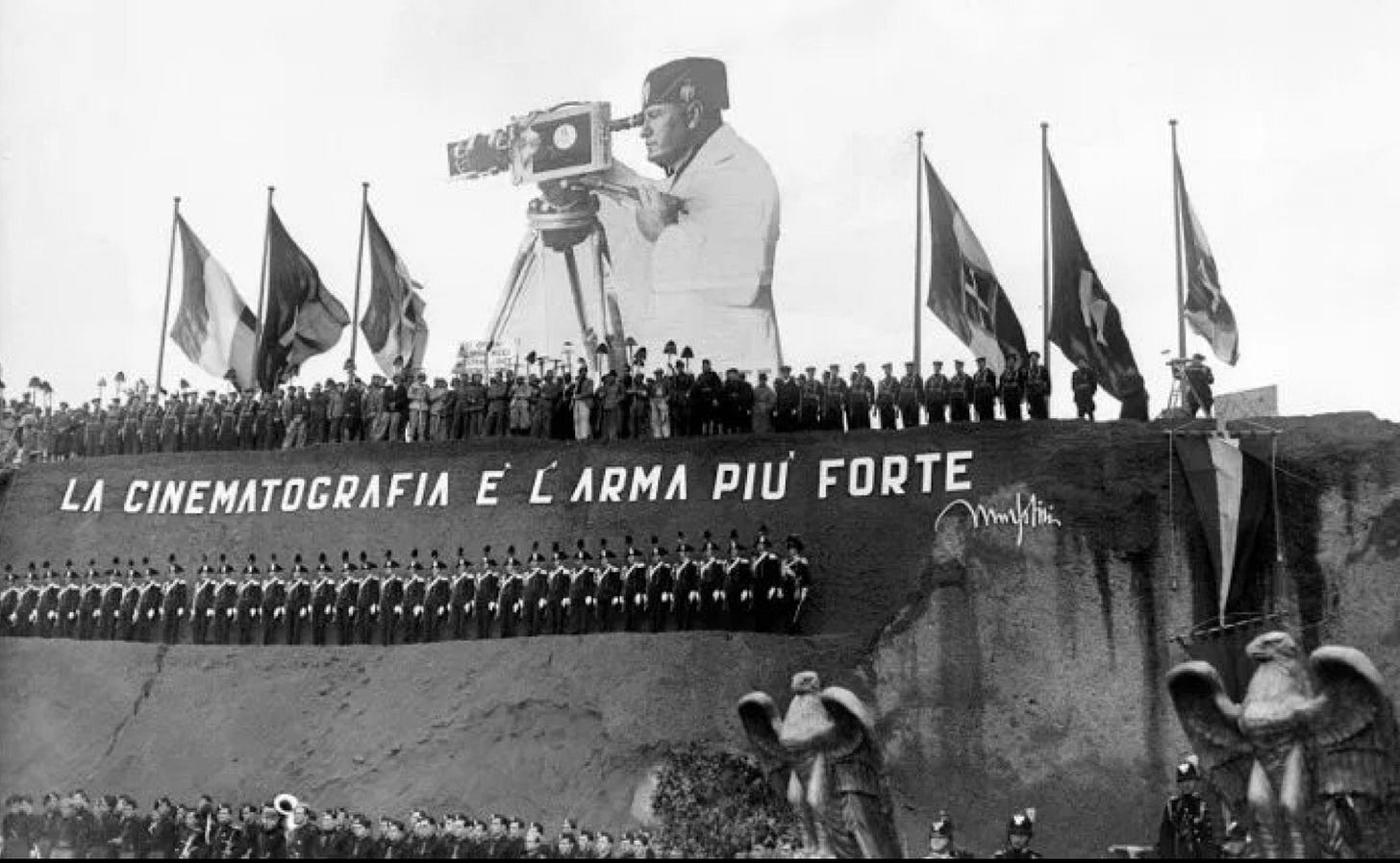

At the tail-end of the Second World War, and in its immediate wake, Neorealism was a dramatic reaction to the grandeur of the early films—precursors to the Sword-and-Sandal epics— made at Cinecittà Studios in exaltation of Fascist ideals. The first of these was Scipione L’Africano (1937) with its tale of Scipio’s triumph over Hannibal. The message was clear: Mussolini was, to coin a phrase, making Rome great again. The production of Scipione was overseen by Mussolini’s son, Vittorio, and heavily financed by the Fascist government. Mussolini had presciently grasped the importance of the nascent medium of sound-era cinema with the motto “La cinematografia è l’arma più forte" (Cinema is the strongest weapon).

Neorealism would be the very antithesis of the vast sweeping historical epics of Roman triumph favoured by the Fascist government. This was not only an ideological rejection of the Fascist regime, and it most definitely was, but was also borne of practical reasons: Cinecittà was among the many targets hit during the Allied bombings of Rome which precipitated the fall of Mussolini and subsequently the sprawling studios were used as camp for displaced persons until 1947. As the war drew to a close both film and studios were in short supply.

A couple of years before Ladri di Biciclette, one of the first examples of a Neorealist feature film is Roma Città Aperta, directed by Roberto Rossellini and with a screenplay co-written by the then twenty-four year old Federico Fellini. What became the characteristic aesthetic of Neorealist cinema was initially determined by practicality: the only pieces of film Rossellini could get hold of were of poor quality or expired and required a lot of light. Thus much of the filming took place outside on location and scenes had to be short. The film tells of the Resistance and is set during the Nazi occupation of Rome. Filming began in January of 1945, before the end of the war and with all of the consequent difficulties that brought, and the movie was released in September of 1945 in the immediate wake of peace.

Some scenes are of poor quality but the lack of available film meant they couldn’t be filmed again and were left as they were. Neorealism may have, in the first instance, broken with the studio tradition out of necessity, but the use of external locations saw sites chosen in sharp contrast to the romance and grandeur of the city’s famous monuments and an unpolished finish was suited to a focus on stories of ordinary people. The still warm bomb sites of the wounded city provided the backdrop to a war which we are not shown on the battlefields but which enters into the daily life of the characters. The tale is tragic, though not told without humour, and was based on events which were still painfully fresh in the memory.

After twenty years of Fascist-sponsored cinema with its relentlessly heroic overtones, this harsh realism both in subject and method was revolutionarily, and often unpopularly, different. Today these are well-loved lynchpins of Italy’s postwar cultural landscape, but initially public reaction was negative: Roma Città Aperta was eschewed by Catholic sensibilities at odds with a priest coming to the aid of Communists, and the representation of desperate poverty in Ladri di Biciclette was seen as washing Italy’s dirty laundry in public. After the opening projection of Ladri di Biciclette at the (sadly now defunct) Metropolitan Cinema on via del Corso irate spectators demanded their money back.

Perhaps even they softened for a moment during one of the most memorable scenes of Ladri di Biciclette which, apparently at least, offers a warm glimmer of hope. During the search for his stolen bicycle, Antonio takes his young son Bruno to a trattoria (on Passeggiata di Ripetta, sadly no longer there). They eat mozzarella in carrozza and drink wine—what would your mother say?—as a cheerful band plays. Bruno emulates the supercilious boy at the next table and pulls the fried cheese with his teeth. There is a moment of real optimism buoyed by fried cheese and music, and with a glass of wine in his belly Antonio says A tutto si rimedia, meno che la morte (everything can be fixed, except death), but a moment later we see the food turn to ash in his mouth as he is reminded once again of the impossibility of his situation.

Food plays an important part in many Roman movies, and with that mozzarella in carrozza in mind, Rachel Roddy and I began discussing Roman films and food. The result, plotted over coffees and spritzes, is our Roman Film Jaunt which will be on Friday 16 May from 10am until 3.30ish.

Rachel and I will be wandering through a couple of our favourite neighbourhoods which feature in Roman movies we love including Caro Diario, Il Pranzo di Ferragosto, Mamma Roma, Ladri di Biciclette, Lo Chiamavano Jeeg Robot, & C’è Ancora Domani. We’ll chat about these films (and others), and there will be ample and suitably-themed snacking along the way, and our final destination is, of course, a slap-up lunch.

There are twelve spots and the total cost including all food and drink is €180. Participation also includes an introduction to the featured films with Rachel and me on Sunday 6 April at 6pm Rome time (a recording will be available) and a map specially designed for the occasion. To book please email info@understandingrome.com. Come, it’ll be a blast!

Saluti da Roma,

Agnes

This sounds fabulous, what larks, Pip! I wish we could be there. Lucky participants.

Oh my goodness, this new walk is going to be such terrific fun for those 12 lucky participants!! Love the theme, and with the two of you leading the way, it’s guaranteed to be fun! ☺️🙌