The mountains of Lazio were once the bed of a tropical sea, long since gone, which was dotted with islands surrounded by coral reefs. Geologists call it the Sea of Tethys for the Greek sea goddess Thethys, both sister and consort of Oceanus and mother of all rivers and lakes. In this sea, calcite deposits merged with animal and vegetable deposits to form sediment, and somewhere around twenty-five million years ago the Italian peninsula began to form. The slow movement of the continental crust squeezed this erstwhile sea bed and approximately five million years ago the Monti Simbruini, limestone and rich in marine fossils, were formed.

Yesterday my pal Rachel Roddy and I took a very jolly band out there for a jaunt. Beautiful views, glorious frescoes, and lots of excellent food and wine all under the blues skies and scudding candy floss clouds of an idyllic May day.

The frescoes we admired were at the exquisite complex of the Sacro Speco—the Holy Cave—where one and a half millennia ago Saint Benedict of Norcia retreated in prayer, disillusioned by the iniquities he had found in Rome. This remote site in the mountains (it is six hundred and forty metres above sea level) is where Benedict subsequently wrote his Rule which would form the foundation of Christian monasticism.

As ever when I take folk there I was in contact with Dom Maurizio, the ineffably affable monk-custodian of the site. He advised strategic timings to avoid the eight busloads of schoolchildren he was expecting on this sunny Friday in May. And so, as if by magic, we arrived as the last group of excited ten year olds were leaving, the morning opening hours extended just for us. As planned, we had the churches all to ourselves in glorious peace before Dom Maurizio arrived with his bunch of keys to take us into the monastery to see the frescoes of the refectory and some even more spectacular views. St Benedict and Whatsapp: a winning, if improbable, combination.

The complex built upon the site of Benedict’s meditations is a higgledy piggledy jumble of manmade construction and chapels hewn into the rock. There are two churches, one atop the other (though both are also on more than one level), and a series of chapels and grottoes linked by staircases. It all sits atop a tall rocky limestone cliff dominated by a tower and supported by nine vast arches.

The first church built against the Sacro Speco, now called the Lower Church, was completely remodelled in the thirteenth century. The Chronicles of the Abbey recount that between 1244 and 1276 an Abbot called Enrico oversaw this work and painting was carried out at least in part by a certain Magister Consolus and his workshop.

A surviving painting from earlier in the thirteenth century tells us about all the work that would follow. On the left, the picked-at plaster of the fresco is an indication that this part subsequently painted over (hacking at the plaster provides a rough surface to which another layer of fresco can be attached). This later fresco was removed to reveal St Benedict and Abbot Romanus

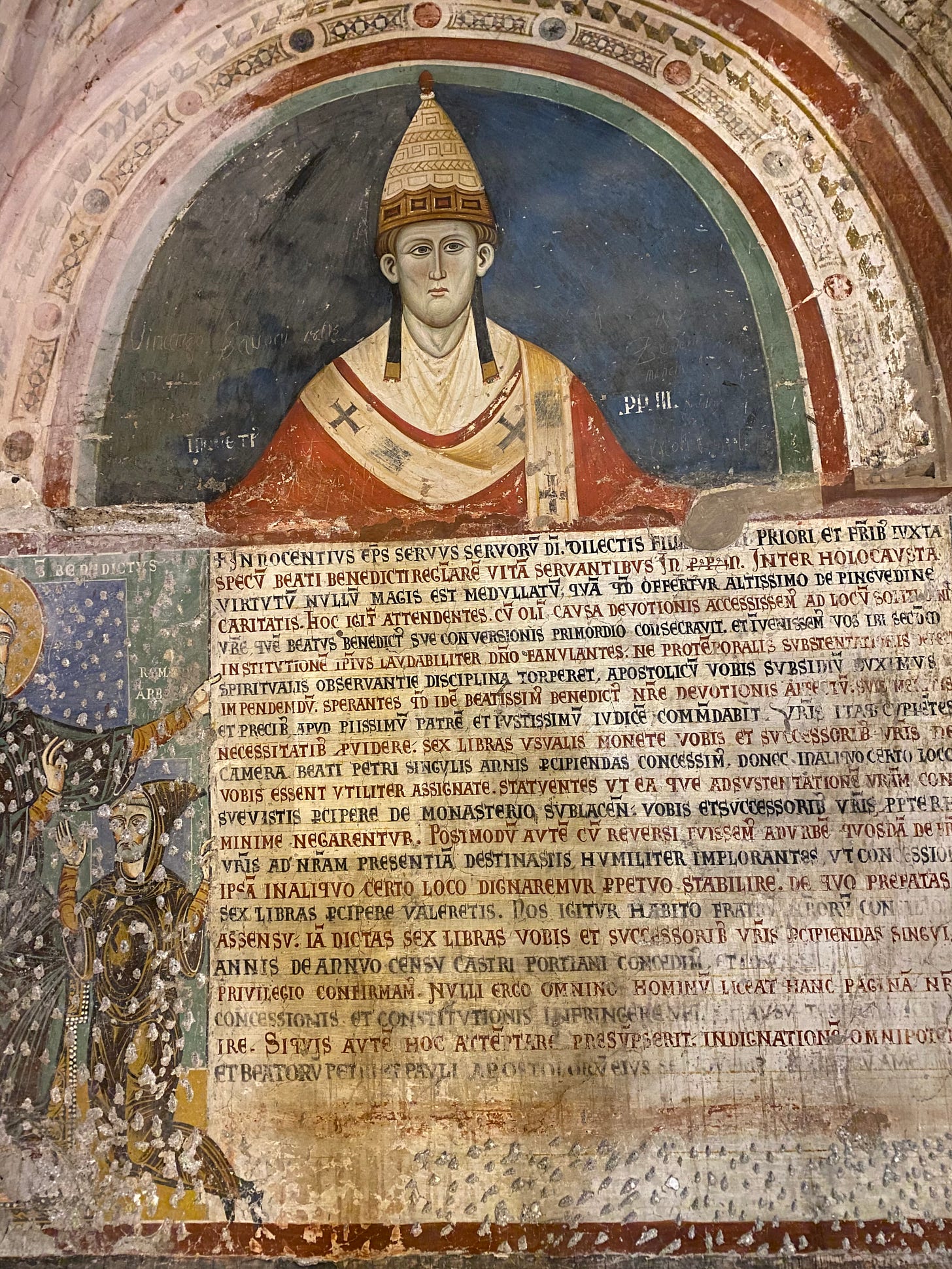

It’s slightly tricky to see, but the small hooded figure of Abbot Romanus on the left of the photo above is shown with a blue nimbus around his head. This indicates that he was alive when it was painted. To the right, Pope Innocent III holds his Papal Bull of 4 July 1202 with which he gave significant donations to Benedictine Monastery at the Sacro Speco, and which would sponsor the major rebuildings from the thirteenth century onwards. Both Romanus and Pope Innocent died in 1216, giving a date before which, given the nimbus, the painting must have been carried out.

The Lower Church is decorated with a series of miracles of St Benedict, one of which is believed to have taken place at the little spring-fed lake where yesterday we enjoyed a delicious spring aperitif chosen by Rachel in dappled sunlight by crystalline waters with not a soul about: fresh broad beans, two sorts of extremely delicious hard cheeses, and some natural fizz from Emilia-Romagna.

The miracles of St Benedict are recounted by Gregory the Great in his life of the saint, written circa 600 CE, half a century or so after Benedict’s death. Further detail was added by Jacopo da Voragine in his Golden Legend of circa 1260, the ink barely dry when these walls were being plastered in preparation for these paintings. One miracle told in the Golden Legend, and shown the photograph below, saw Benedict bless his follower St Maurus that he might walk on the waters of (probably) this Laghetto to rescue St Placidus who had fallen in. We, happily, had no need of such divine intervention on our foray to this bucolic sylvan spot.

In the ceiling vaults above we see a hierarchical chain of divine inspiration. If we begin with the most earthly we see St Benedict, holding his Rule, and surrounded by pope- and bishop-saints.

Another vault shows Christ in the central roundel, surrounded by a floral motif. and alternating apostles and archangels. St Peter is shown in a characteristic representation at the bottom, at the top the bald head belongs to St Paul, not one of the original twelve but called by Christ after the Resurrection the “Apostle of the Gentiles”.

And in the third vault, the top tier of divinity is reached: we see a representation of the Agnus Dei—the Lamb of God—surrounded by the evangelists. Below we can just glimpse the head of Matthew, shown as an angel, and Mark, shown as a lion. Around the lamb, painted decoration emulates the Cosmati stone inlay favoured in church flooring at the time.

In the lower chapel of the Lower Church, dedicated to the Virgin, we can see such a floor, once again created using stone repurposed from the nearby ruins of the Villa of Nero.

This chapel is reached by the Scala Santa, the Holy Staircase, so called because it follows the route Benedict climbed to reach the Sacred Cave.

The decorations of the Holy Staircase date to the fourteenth century, contemporary with the Chapel of the Madonna. Images of hermit saints include hairy old St Onofrius, a fourth century anchorite who lived in the Egyptian desert.

Another Coptic hermit saint is brought in to introduce the theme of death as the implacable arbiter of destiny: St Macarius shows young gadabouts the three stages of decomposition as they ignore him in favour of their falconry chat. On the opposite wall, its undulations reminding of the rock face behind, this macabre theme continues.

Death charges on horseback towards the young noblemen, trumpeting doom laden prophecies to the faithless, and sparing the pious folk on the right. The nobles are oblivious to his arrival, more concerned with the mundane trappings of earthly wealth. Falcons are a recurring motif: the ultimate accessory for the fifteenth century man about town. It is a solemn memento mori for the devout.

The faithful, then, once would have come from the valley below. This would have been a near vertical slog at the end of a long and arduous journey leading to the valley of the River Aniene. We, instead, arrived in an air-conditioned Mercedes van driven with calm aplomb by my favourite driver. But we could imagine the journey of those pilgrims.

They once arrived at the bottom of the complex at the Grotto of the Shepherds, where Benedict first received followers after his period of solitary contemplation. Here we see the fragments of the oldest of the frescoes here, an eighth century Virgin and Child.

They would continue their pilgrimage up the Holy Staircase to the Lower Church and the lower part of the Holy Cave itself, decorated with miracles from the life of the Saint and in the vaults about that divine chain of command from Benedict through Christ to the Holy Spirit.

The pilgrim would then continue up to the highest part of the complex, and the last to be built: the Upper Church. Abbot Bartholomew II, abbot in the first half of the 14th century, enlarged the complex in part incorporating existing structures, in part demolishing and rebuilding to create a larger church, and one that was on a single level. In the 1360s Abbot Bartholomew of Siena (he’s a different one, just also called Bartholomew) called Sienese artists to paint the first section of the church.

These are scenes of the Passion, culminating in the Crucifixion which leaves unspoken its natural corollary: the promise of Resurrection. The complex of the Sacro Speco offers a spiritual crescendo of hope which mirrors the physical climb undertaken by so many weary pilgrims.

Next time I’m in Rome I want to go there with you

We were walking in your footsteps in Subiaco yesterday and the revisiting after about 30 years was certainly worth it. Your hinting at the restored fresco’s of the refettorio made me ask for it at the sagrestia. Although I had made no reservation to get access, fortunately it was not busy at all (37 degrees C, who would have thought to go there but us..). The organist/guide was willing to go there with us, so we had a very private visit to this closed part of the monastery. And it was a marvel to see these almost pristine fresco’s.