Photographs taken on 5 December 2024

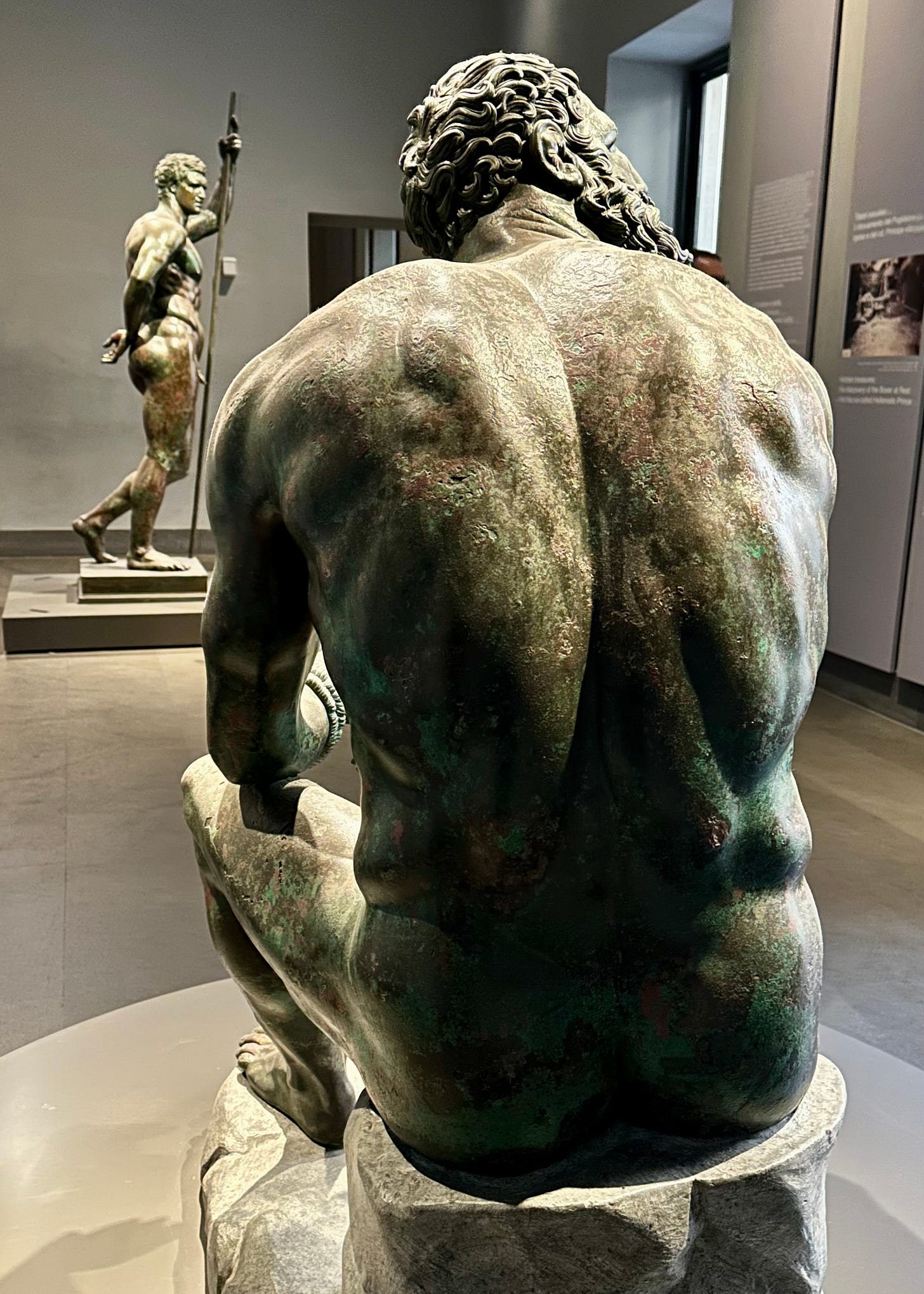

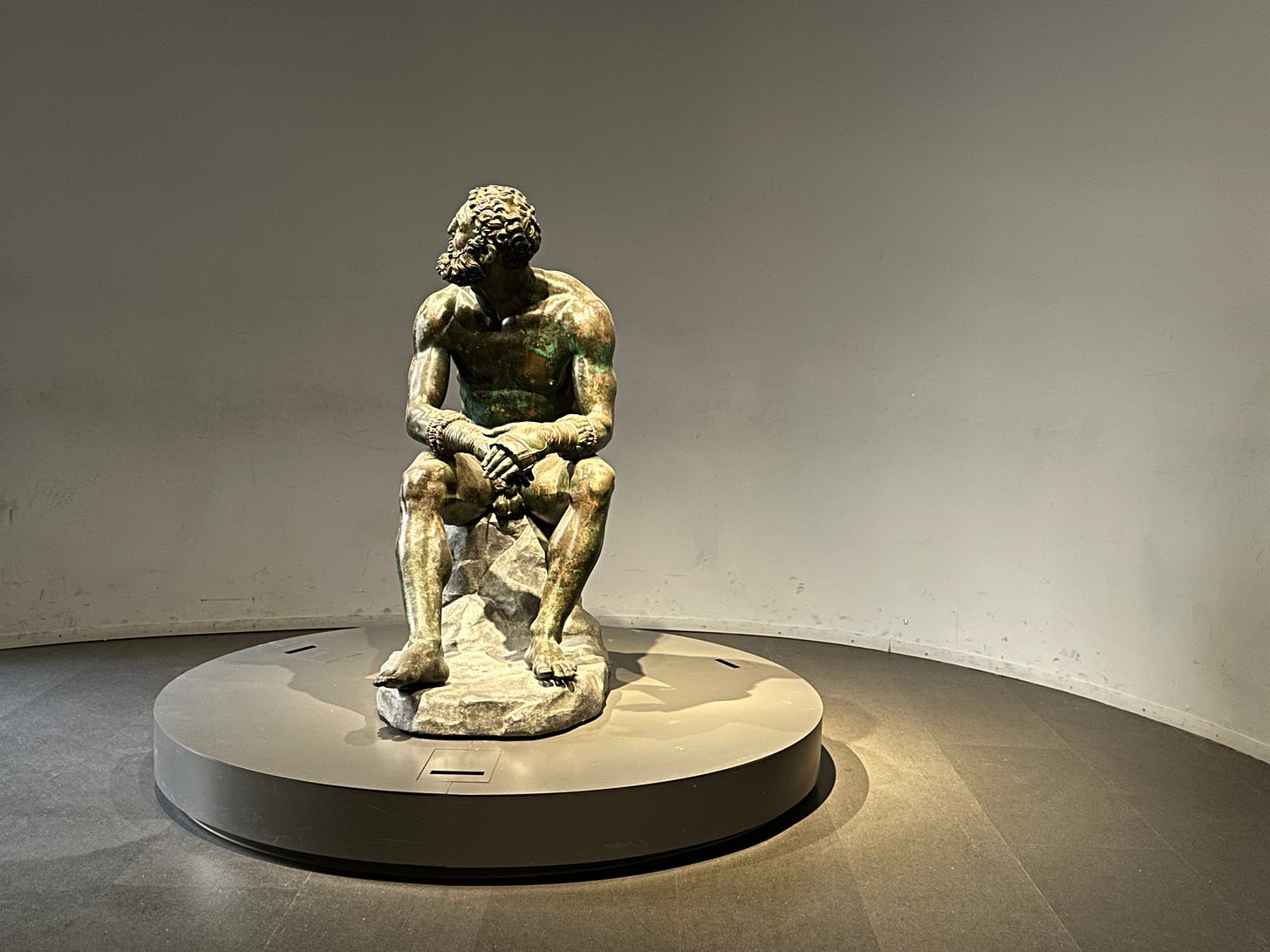

I often think that Rome quite simply has far too many extraordinary things, a veritable galaxy without end; places and objects which would be the most celebrated in any normal city are all too often overlooked. One such piece is the glorious, moving, bronze sculpture of a boxer, a forgotten hero quietly sitting in Room VII of the excellent Museo Nazionale Romano at Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, where you can usually have him all to yourself.

The Boxer was found in 1885 as large sections of the Quirinal Hill were being cleared to make way for the building boom of the new capital city. Rome had shaken off the mantle of her own—papal—ancien régime and entire new quartieri were being built to house ministries and mandarins; cogs in the machines of the nascent Italian state.

One of the archeologists responsible for saving so much of what might have otherwise been lost in the rush to build the new, secular, capital was Rodolfo Lanciani. As areas of the former Baths of Constantine on the eastern slopes of the Quirinal were being cleared under his supervision—where we now find via IV Novembre—an extraordinary figure revealed himself to have been sitting, patiently, under the rubble and mud of centuries. Lanciani recorded the event thus:

I have witnessed, in my long career in the active field of archeology, many discoveries; I have experienced surprise after surprise; I have sometimes and most unexpectedly met with real masterpieces; but I have never felt such an extraordinary impression as the one created by the sight of this magnificent specimen of a semi-barbaric athlete, coming slowly out of the ground, as if awakening from a long repose after his gallant fights.

Plausibly attributable to a Greek artist of the mid-first century BCE the glorious, late Hellenistic, bronze of a boxer at rest is, I think, one of the most poignant sculptures in Rome.

Writing in the second century CE, Pausanias’ “Description of Greece” tells us that already at the fifty-ninth and sixty-first Olympiads—in the sixth century BCE—statues were erected to honour victorious athletes and amongst these was a representation of Poulydamas, an exponent of the pankration, an unarmed fusion of boxing and wrestling with no holds barred.

We can, then, perhaps see our boxer in Room VII as a successor to Poulydamas. Certainly the detail of depiction suggests anatomical study of one or several fighters; if not a portrait of an individual it is then perhaps a hybrid providing the essence of a weary fighter.

At first we see a muscular figure seated in apparent relaxation, his hands bound with leather straps—himántes. But look closer and his head, turned towards something we cannot see, tells us this is no triumphant athlete. His cheek is split and his head is bleeding from very recent wounds, superimposed upon older injuries, the details engraved and picked out in applied copper.

Realistic details include a ring through his foreskin, to keep his penis out of combat for both practical and aesthetic reasons.

His nose has been broken and re-broken, and his misshapen ears bear the signs of multiple fights. This is no generic exaltation of athleticism but an extraordinary psychological study of an ageing boxer nearing the end of his career, as we see him turn wearily, perhaps called back into the ring once again.

I had this marvelous fellow all to myself for about 15 minutes last year. I finally realized that I couldn't look at him without my eyes becoming watery. If that doesn't tell of the power of art, I don't what does. This post brought me right back there again. There's power in that too, Agnes. Thank you as always.

I looked at him and wept.