Vespa Tunes XIX: Bartali, Paolo Conte, 1979

Central Rome is presently festooned with yellow tape discouraging parking and pink signs with arrows indicating the route of the final stage of the Giro d’Italia which is this year concluding in the capital. The Giro d’Italia began in 1909, six years after the Tour de France and pink is the colour of the Giro in recognition of the pink pages of La Gazzetta dello Sport which has organised the race since its ideation.

In fact the conclusion of the race in Rome is unusual, it only finished here for the first time last year. It more often ends in Milan, where La Gazzetta is based, but Rome puts on a good show and this year once again, just before seven o’clock this evening, the final stage will end by the Colosseum.

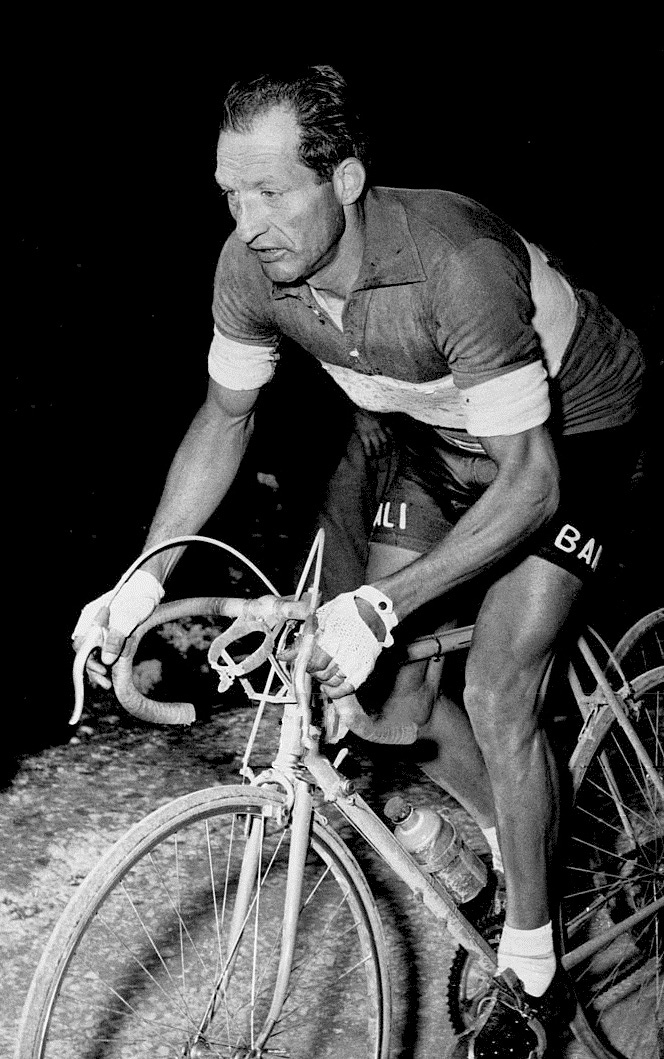

All of this brings to mind Paolo Conte’s paean to Gino Bartali, winner of the Giro in 1936 and 1937, and of the Tour de France in 1938. Extraordinarily he went on to win both races once more after a significant wartime hiatus: the Giro d’Italia in 1946 and the Tour de France in 1948. When he married in 1940 his wedding was blessed by Pope Pius XII, that’s how famous he was. Bartali died in May 2000 aged 85, I had then been in Rome a few months and I remember it was the first I’d heard of him. He was a big deal.

Conte’s song is, of course both about cycling and not. It is redolent of endeavour and humiliation. The concern for what the French think speaks of the long-standing spiky relationship with Italy’s neighbours across the Alps. France, already wounded, had been gratuitously stabbed in the back by the entry of Italy into the Second World War as an ally of Germany in 1940. Bartali — a consistently and bravely staunch anti-Fascist — is a figure offering atonement for Italian post-Fascist shame and humiliation. He was beloved by all stripes of Italians, his post-war victories were said to have averted civil war.

A devout Catholic, Bartali rode messages and false identity documents for Partisan organisations throughout central Italy, all the while wearing a shirt with his name on: such was his fame that no one stopped him. Eventually he was questioned by the Nazi and Fascist authorities and his life threatened. This courage, that he hid a Jewish family in his cellar, and helped save many many more only came to light after his death. In 2013 he was recognised by the Holocaust memorial organisation Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations.

Conte’s glorious, onomatopoeic poetry wears its erudition very lightly and doesn’t really translate. I’ve gone for the gist. His is a careful and clever use of vocabulary — the archaic exoticism of “caucciù”; the dated modernity of “cellophane”, one can just hear the crinkle; the surreal evocation of Bartali’s battered nose: quel naso triste come una salita (a nose as sad a climb), quel naso triste di un italiano allegro (that sad nose of a happy Italian). Plus it’s an excellent tune, I just love it and shall be humming it as the cyclists make their way from the coast to the Colosseum this afternoon.

Farà piacere un bel mazzo di rose

e anche il rumore che fa il cellophane

ma una birra fa gola di più

in questo giorno appiccicoso di caucciù.

A nice bunch of roses are pleasing

and the sound of the cellophane

but a beer is more satisfying

in these sticky days of rubber1

Sono seduto in cima a un paracarro

e sto pensando agli affari miei

tra una moto e l'altra c'è un gran silenzio

che descriverti non saprei.

I’m sitting on a bollard

minding my own business

between one motorbike and the next there is a deafening silence

that I can’t describe

Oh, quanta strada nei miei sandali

quanta ne avrà fatta Bartali

quel naso triste come una salita

quegli ochhi allegri da italiano in gita

e i francesi ci rispettanoChe le balle ancor gli girano

E tu mi fai: "Dobbiamo andare al cine"

"Vai al cine, vacci tu"

Oh how far I’ve come in my sandals

How far Bartali will have come

that nose as sad as a climb

those sparkling eyes of an Italian on a day out

and the French respect us

though they’re still pissed off

and you say “We have to go to the movies”

“Go to the movies then, go!”

È tutto un complesso di cose

che fa sì che io mi fermi qui

le donne a volte sì sono scontrose

o forse han voglia di far la pipì.E tramonta questo giorno in arancione

e si gonfia di ricordi che non sai

mi piace restar qui sullo stradone

impolverato, se tu vuoi andare, vai...

It’s a mix of things

that makes me stay here

women are sometimes grumpy

or maybe they just need a pee.

And an orange dusk descends

and the day fills with memories that you don’t know

I want to stay here on the dusty road,

if you want to go, then go…

e vai che io sto qui e aspetto Bartali

scalpitando sui miei sandali

da quella curva spunterà

quel naso triste da italiano allegro

tra i francesi che si incazzano

e i giornali che svolazzano

C'è un pò di vento, abbaia la campagnae c'è una luna in fondo al blu...

So go because I’m here waiting for Bartali

pawing the ground in my sandals

from behind that bend will appear

that sad nose of a happy Italian.

Between the French who are pissed off

and the newspapers in a flap.

There’s a bit of wind, the countryside howls

and there’s a moon at the end of the blue…

Tra i francesi che s'incazzano

e i giornali che svolazzano

e tu mi fai - dobbiamo andare al cine -

- e vai al cine, vacci tu! -

Between the French who are pissed off

and the newspapers in a flap

and you say to me - we have to go to the movies -

- so go to the movies, just go! -

“caucciù” is an Italianisation of the French term “caoutchouc” coined by the French naturalist and explorer Charles Marie de La Condamine for natural rubber found in the Amazon basin and first brought to Europe in 1736. The word in turn came from the Quechuan name “cao tchu” (meaning rainforest).

Not only was Bartali an outstanding athlete, but also, an incredibly brave man as you described. The Alberto Toscano biography is a pacy engaging read - I highly recommend it.

I do enjoy receiving your posts. Cheerio - Paula

Paula Nathan, AO

wonderful! thank you agnes for sharing this.